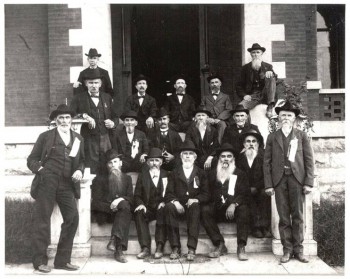

A picture hangs on my living-room wall in Columbia, Tennessee, magnificently framed, of which I am especially proud. It is an original 1902 photograph of Confederate veterans gathered for a reunion — friends, relatives, and comrades-in-arms of my great-grandfather James Lewis White, a private in Company F of the 48th Tennessee Infantry, who later enlisted in Company F of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry.

Front row: William “Rafe” Gresham (standing), (?), George William Park, Newt. G. Cockrill, William A. “Bill” Davidson, John Davidson (slightly back of Bill), William Hezikiah Mitchell (standing). Second row: William Henry “Bill” Watson (standing), Andrew D. Bryant, James F. Agnew, James M. “Jim” Gilliam, David Frierson Watkins. Third row: (?), Andrew Elijah “Andy” Denham, James Anderson Vincent. Top row: John Nelson Meroney, (?).

The picture is probably taken in Nashville for it bears the embossed logo of Giers Art Gallery, established in 1855 by Carl Giers, the famous German-born photographer of Southern politicians and generals. Most believe this was taken on the courthouse steps in Dallas but this building does not favor the courthouse at all.

My personal copy of the picture was given to me by my dear friend and second cousin once removed, Earl Thomas “Tom” Gilliam of Columbia. Jim Gilliam, above, was his great-grandfather. The Davidson brothers pictured were his grandmother’s uncles and my great-grandmother’s brothers (brothers-in-law to James Lewis White).

The reunion photo was Tom’s most prized possession. He is the one who had it impeccably framed with a brass plate identifying the veterans. Furthermore, through the years, he had painstakingly written notes about most every man pictured. Additionally, as he wrote, he no doubt consulted with his wife from time to time. Dorothy “Dot” Westmoreland Gilliam, co-author of Hardison and Allied Families, was one of the finest genealogists produced by Columbia, Tennessee – a town rich with exceptional genealogists and historians.

I was always curious about the men and the reunion. Who were they? Where did they serve during the war? How did they fare after the war? What were their occupations? How did they get to the Dallas reunion? What did they do once there?

So, after years of procrastination, I looked through Tom’s notes and Dot’s old files to piece together a story. It turns out, the occasion was a four-day United Confederate Veterans convention in Dallas, Texas (April 22nd through the 25th). Several of the men belonged to the 200-member consolidated U.C.V. chapters, Leonidas Polk Bivouac #3 and William Henry Trousdale Camp #495. They met at the Columbia courthouse every first Monday of the month at 11 a.m. to accommodate country members who came to town on that day for the monthly stock sales.

They were on their way west via the N. C. and St. L. Railway which ran through their community of Maury County, Tennessee. “One Cent Per Mile” read the advertisement in the Confederate Veteran Magazine, which meant they could make the roundtrip for about $13. Headquarters for the reunion was a huge tent pitched by the Oriental Hotel, hosted by staff and volunteers of the Confederate Veteran.

This was the “twelfth general reunion” of the U.C.V. and the crowds had grown and grown. By this time, across the South there were 1,408 U.C.V. camps with applications for another 100. In Dallas, a multitude had gathered of whom only 12,000 were veterans. Gradually the events had evolved into festivals where Southerners came to pay tribute to veterans, the memories “of the fallen brave and to promote comradeship.”

An article from the Los Angeles Herald describes the affair:

REUNION OF CONFEDERATES

Hosts of Veterans Gather at Dallas

The Only Survivor of Jeff Davis’ Cabinet Present

The Crowd Sang “Dixie,” “The Star Spangled Banner,” “Bonnie Blue Flag” and “America” and All Were Cheered With an Equal Ardor

DALLAS, Tex., April 22. —With the confederate reunion officially twelve hours old, it is estimated tonight that there are 125,000 visitors In Dallas. It is estimated that there were 80,000 visitors at the camp in the fair grounds today. An additional influx of visitors is expected tomorrow, the attraction being the Kalliph’s parade.

An immense crowd was present tonight at the ball given at the camp by the Sons of Veterans. While thousands of visitors did not leave the business section of the city, the tents of camp Albert Sidney Johnson, two miles distant, were crowded. The great mess shed, seating 12,000, was opened this morning. An army of cooks and waiters worked like beavers, while the veterans, with a hunger born of a night in the open air, did their best in an endeavor to keep the cooks busy.

The convention building, seating 8,600 people, was filled soon after the veterans were called to order by Gen. K. M. Van Zandt, president of the Texas veterans. Chaplain Young delivered the Invocation and Gen. Joseph D. Sayers, on behalf of the state of Texas, welcomed the visitors.

Mayor Ben T. Cabel welcomed the veterans to Dallas and Hon. T. G. Gerald of Waco delivered the welcome on behalf of the confederates of Texas. William McCamy welcomed them on behalf of the local societies of veterans, and Col. W. L. Crawford spoke for the Texas reunion association and local veterans. Interspersing the speeches the songs of the southland were mingled with those of the whole nation. They were sung in this order; “America,” “Bonnie Blue Flag,” “Dixie,” Star Spangled Banner,” “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” and again the undying “Dixie.” All were cheered with equal ardor.

The “Kalliph of Bagdad” and his retinue were present in all their splendor. Among those on the stage were Judge John H. Reagan, the only surviving member of the [Jefferson] Davis cabinet, and Miss Lucy Lee Hill of Chicago [General Ambrose P. Lee’s daughter] , the sponsor in chief of the United Confederate Veterans.

At 11:15 p. m. Commander in Chief Gordon arrived, twenty hours late. Thousands of people lined the streets during the afternoon and witnessed the arrival of the Kalliph. The Kalliph and his gorgeous subjects, followed by carriages containing General Gordon and other distinguished veterans, Governor Heard of Louisiana and Governor Sayers of Texas, by bands and militiamen and trumpeters, proceeded through the streets to the official reviewing stand, near the post office, where Mayor Cabell in a grotesquely sober speech deferentially presented an immense gilded key to “his majesty.” The Kalliph, in turn, handed the key to General Gordon, thus giving to that veteran the suzerainty of the city.

In 1902, these men – most of whom were in their sixties – had survived the war, the hardships of returning penniless to a pillaged homeland, the humiliations and deprivations of martial law during Reconstruction, and a national depression in the 1890s. They truly were tough, rugged, remarkably resilient men.

The following excerpt from an 1866 Columbia Herald editorial describes the political reality to which they returned:

Tennessee to-day is the most unfortunate state on the continent cursed as never was a State, by a band of political outlaws, who accidentally occupy official positions ; her people impoverished by four years war, her limbs shackled and bound by infamous enactments, called laws — she is certainly deserving of the pity of all the world. “We venture the assertion that, since the first attempt at representative government, history contains no record of just such a body acting in a legislative capacity, as is now assembled at Nashville. As representatives, they cannot truthfully claim five thousand constituents in the State. In point of information, integrity and respectability, they represent about the same number, and generally the same persons, as do the inmates of the State Penitentiary and Insane Asylum. It can be established before any honest jury of twelve disinterested and impartial men, that three-fourths of that body have already been guilty of willful perjury. “While this is so, it excites no remark, simply because it astonishes no on acquainted with the private character of the individual members.

It is not, therefore, a matter of surprise that such a body, imbecile, incompetent,and bent on plundering the coffers of the State, should seek to perpetuate their hold upon the public offices. Their chief aim is plunder, and to gain this they have hesitated at nothing, and will be deterred by none of the considerations that usually operate to control, or govern, the actions of honorable men.

Incidentally, times were bad for most people in the South. In the same edition, mention was made of two young African American children who were drowned in a pond on Captain Andrew Jackson Polk’s old property. Their mothers had drowned them because they could not take care of them after they had been freed from slavery.

Winnie Estes Sowell, William H. Mitchell’s granddaughter, describes life after the war:

…So it was my good fortune to learn at the knee of a living witness of the great struggle that the subsequent battle of reconstruction was an even greater test of courage, fortitude and stamina than the actual conflict of arms. The returned veterans literally had to start from scratch. There was scarcely anything left upon which to build except the scorched earth. Yet I never heard my grandfather complain, condemn, criticize or show signs of bitterness. He and his bride took up their burden philosophically and proceeded to “multiple and replenish the earth.” They were married in the autumn of 1865, she a blue-eyed belle of Scotch-Irish parents and was doubtless the source from whom most of us inherited dancing feet and musical talent…”Billy and Sally” established their modest love cottage on a small farm. Furnishings were scanty. That was before the day of kerosene lamps. They made their own candles and were otherwise resourceful and ingenious. Of course they had a spinning wheel and other “conveniences” of the period. They were thrifty, energetic, congenial, temperate in all things and religious. The Bible was their chart and compass. So they prospered. They soon owned one farm, then another, and finally three. Eight children attest to their prosperity. All of them were educated and otherwise fared better or easier than their parents.

After surviving Reconstruction, there were other challenges ahead. In 1893 came the national banking crisis caused by an over-expansion of railroads compounded by a panic in the gold and silver markets. All three banks in Columbia closed. Many prominent families were either ruined or saw their net worth cut in half (two of the three banks were able to pay depositors 50 to 57 cents on the dollar). Yet “the men in the picture” survived and some even prospered. Here are a few brief biographies:

William Hezikiah Mitchell (1838-1920) was the grandson of William and Betsy Dabbs Mitchell, Virginians who came to the Culleoka community in 1809.

William Hezikiah Mitchell (1838-1920) was the grandson of William and Betsy Dabbs Mitchell, Virginians who came to the Culleoka community in 1809.

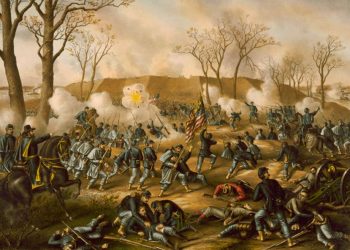

Mitchell kept a war diary. He tells about the 1st Tennessee which was originally under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forest but reassigned to Colonel (later Brigadier General) Fightin’ Joe Wheeler in October of 1862 through end of the war. They engaged in some of the hardest-fought battles of the war – Shiloh, Chickamauga, at New Hope Church, and Resaca, the Battles of Franklin and Nashville, then Savannah, Georgia before driving back north to Chapel Hill.

In April of 1865, as 1st Sergeant of Company F of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry, Mitchell was “detailed to take a scouting party of three men” to determine the whereabouts of Sherman’s army. He selected Alfred Gardner, George Park, and W. C. “Frank” Aydelotte:

We had not then heard that Johnston had surrendered to Sherman. We went as ordered. We struck a creek, probably about 3 miles from Chapel Hill, N. C., crossed creek and struck a lane leading to a main road, leading in the direction in which Sherman’s army was supposed to be marching.

We saw a company of Federals coming down the road towards us. There were only four of us, but we saw we could not run, so we tried a bluff game, and we raised a yell and charged them. They ran. As we hoped they would do, and we ran them back down the road to an old man’s house that they had plundered. The old man told us which way Sherman’s army was moving.

We went back to report the information we had received, and were ordered with our whole squadron, to return and hold the ford of the creek…

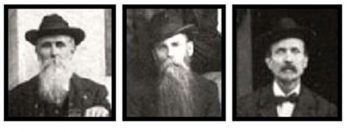

This action was considered the last scouting party sent out by Joe Johnston’s army, and “the last charge” – four against 100. Forty-five years later, the four met for the first time as a group on the courthouse square of Columbia, and had their photographs made (above).

Mitchell’s great-grandson, Baker Mitchell, Jr., told of their last days of service:

[They] stacked arms on May 2 in the yard of Sugar Creek Church near Charlotte, were paroled on May 3, and started home to Maury Co. Tennessee with the silver Reales pieces handed out by Joe Johnston on May 4, 1865. Thus ended their four years of war that began with their enlistments at Ashford Hall in Maury County on July 5, 1861.

Davis, escaping to New Mexico, instructed Johnston to send him the war chest with 39,000 silver Mexican 8 Reales pieces so he could use it to raise a new army out West. Instead, Johnston divided the Confederate treasury “among the troops irrespective of rank, each individual receiving the same share” as they “had received no pay for many months.”

One of W. H. Mitchell’s best friends was David Frierson Watkins (1844-1929). David was the half-brother of Sam Watkins, author of Company Aytch, a book considered by filmmaker Ken Burns and many historians as one of the best Civil War memoirs written by a foot soldier. It is said to have influenced Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage.

One of W. H. Mitchell’s best friends was David Frierson Watkins (1844-1929). David was the half-brother of Sam Watkins, author of Company Aytch, a book considered by filmmaker Ken Burns and many historians as one of the best Civil War memoirs written by a foot soldier. It is said to have influenced Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage.

In the 2007 expanded edition of the book, there is a detail of David from the reunion photograph and a chapter which features a story about him:

[Company H trades fire with a large number of Union soldiers who boast “10 pieces of cannon.”]

…Captain Joe P. Lee orders us to load and fire at will upon these batteries. Our Enfields crack, keen and sharp; and ha, ha, ha, look yonder! The Yankees are running away from their cannon, leaving two pieces to take care of themselves. Yonder goes a dash of our cavalry. They are charging right up in the midst of the Yankee line. Three men are far in advance. Look out, boys! What does that mean? Our cavalry are falling back, and the three men are cut off.

They will be captured, sure. They turn to get back to our lines.

We can see the smoke boil up, and hear the discharge of musketry from the Yankee lines. One man’s horse is seen to blunder and fall, one man reels in his saddle, and falls a corpse, and the other is seen to surrender.

But, look yonder! the man’s horse that blundered and fell is up again; he mounts his horse in fifty yards of the whole Yankee line, is seen to lie down on his neck, and is spurring him right on toward the solid line of blue coats. Look how he rides, and the ranks of the blue coats open.

Hurrah for the brave rebel boy! He has passed and is seen to regain his regiment. I afterwards learned that that brave Rebel boy was my own brother, Dave, who at that time was not more than sixteen years old.

…You could have heard the cheers from both sides, it seemed, for miles.

Sam Watkins, a private in Company H of the 1st Tennessee Infantry (the Maury Greys), was from the Ashwood community of Maury County. Dave and he grew up near the plantations of President James K. Polk’s kin. The Watkins were the third most prominent family in the county’s prosperous planter society. Sam’s father Frederick, a Virginian who came to Tennessee as a young man, owned two plantations and more than 100 slaves.

Sam Watkins, a private in Company H of the 1st Tennessee Infantry (the Maury Greys), was from the Ashwood community of Maury County. Dave and he grew up near the plantations of President James K. Polk’s kin. The Watkins were the third most prominent family in the county’s prosperous planter society. Sam’s father Frederick, a Virginian who came to Tennessee as a young man, owned two plantations and more than 100 slaves.

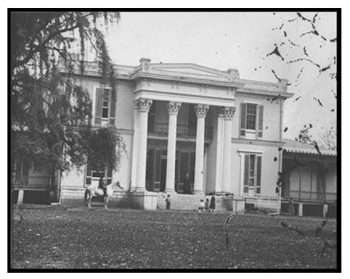

Ashwood was known for fertile and beautiful plantations. There, Leonidas Polk himself (third cousin to the President, an Episcopal Bishop, and a Confederate General) owned “Ashwood Hall” and at least 215 slaves. Some estimate the number closer to 400.

His brother, Andrew Jackson Polk, purchased Ashwood Hall (pictured, right). My great-great grandfather Levi King of Mt. Pleasant, a landowner in his own right, was additionally Andrew Jackson Polk’s overseer. Levi’s father John had the same arrangement with Andrew Jackson’s uncle Joseph. The friendship between the Polks and the Kings dated back to their days in Scotland before coming to America. The families fought side by side in the Revolutionary War.

When the Civil War came, Company F of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry (the Maury County Braves) was formed on the front lawn of Ashwood Hall. Andrew Jackson Polk was the Captain and Levi King was his 1st Sergeant.

As recorded by Sam Watkins in Company Aytch, the men originally signed up for a year’s service, expecting a quick victory and glory on the battlefield; however, he goes on to depict in stark detail a long, drawn-out reality of severe, grotesque deprivation, barefoot boys freezing to death in the snow, starvation, and horrific, bloody mangling and disfigurement by new instruments of war.

The Watkins brothers returned to Maury County in 1865 to a much different way of life. Sam’s last home was the old parsonage at Zion Church. Of course, he wrote a popular remembrance of the war but he had to sell subscriptions for the printing. He died at age 62, less than a year before the Dallas reunion. Dave and his comrades of the Leonidas Polk Bivouac conducted a service with full military honors for his brother at Zion Cemetery.

George William Park (1840-1927) of the “Last Charge,” had been featured in an article in the Columbia Herald, just a year before the Dallas trip:

George William Park (1840-1927) of the “Last Charge,” had been featured in an article in the Columbia Herald, just a year before the Dallas trip:

On the Duck River Valley railway, and over ten miles from Columbia, is Park Station, and a busy little place it is, having a big extent of country to support it; customers and traders coming from all the hills and valleys for miles.

Samuel Park came to the vicinity [from South Carolina] when the country was a cane brake before 1812. His son J.S.A. Park is now seventy-eight years of age, and there are not many old men like him as to vigorous capacity. He was born here and his son, G. W. Park, is the prime mover of the region’s property, as he is a manufacturer in grist, saw and shingle milling, also merchant, farmer, and stock-raiser. Further he is officially post-master, railway agent and express agent. The firm is G. W. Park & Son, and a great deal of the business devolves upon the junior partner Erastus J. Park, who gives the mercantile department and others, energetic attention, and he is a young gentleman of exceptional ability.

The Park farms encompass not far from 250 acres, and are beautifully situated and traversed by Silver Creek, Fountain Creek and three splendid springs. The mercantile house carries an excellent stock, and is selling extensively on the cash basis, which was adopted on the 15th of December.

The Park Mills have twenty horse power and cannot get cars enough to supply orders for logs, lumber and shingles. Park Station is one of the best shipping points on the Duck River branch, and has the people to make it grow and develop the country at large.

W. Park has been in the mercantile business since 1866 and was a gallant member of the 1st Tennessee. He is a thorough business man and can always be found at his offices or within call, which has been an excellent characteristic of the Parks for generations. He is held in high esteem by all who know him and financially and socially he has gained a high reputation as to being responsible in business and a representative gentleman in every respect.

The Park Place” joined my great-grandfather’s property on Silver Creek. Ironically, Mr. Park’s old barn burned down and that of my grandfather’s was torn down in the same year, 2012.

The article was followed by a brief biographical sketch of Rafe Gresham (1841-1911) who lived a mile from Park:

The article was followed by a brief biographical sketch of Rafe Gresham (1841-1911) who lived a mile from Park:

[The Gresham Stock Farm] became the property of Benoni Gresham, who came from Virginia in the early twenties, and its grand location shows that the men of that time loved the beauty of nature as well as good fields and grazing hills. W. R. Gresham, son of the aforesaid, is now proprietor, and he is making it a grand place. The handsome home stands high, and grants fine views, including Park Station, the railway, and miles of Maury County farms.

The big barn measures 100 feet long by 50 wide and is equipped with mule pens, horse stalls, horse power and machinery shelters. Two big cisterns have a capacity of over 1,000 barrels of water, and wells add to the convenience, while trickling down the hills are rivulets.

In the paddocks are some fine colts from Duplex and Hal stock, and in the pens fifty strapping mules are fattening. Sleek cattle roam around and Chester White and Berkshire hogs go a grunting, while poultry add to the farm chorus.

The Gresham Stock Farm shows progress, neatness and plenty. W. R. Gresham is an untiring worker. When I met him he was mixing mortar, and in him it seemed quite gentlemanly. He is as happy always as a summer’s day is long, and is another Maury County farmer who has made farming earn him a competency.

He came back from the army and the 1st Tennessee Cavalry without as much as a nickel. He meant to have kept the Jeff Davis dollar he got at the surrender, but he lost it; he is now worth many thousands.

Gresham’s 333 acres were situated between Park Station and the next stop on the old Duck River Valley Line, Bryant Station. At the time of the reunion, the DRVL had been purchased by the N. C. and St. L. Railway.

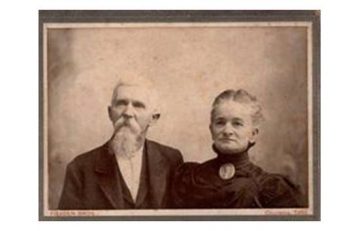

Andrew Daly Bryant (1825-1910) of Bryant Station was according to Goodspeed’s History of Maury County…one of Maury County’s most enterprising citizens, was born in Franklin County, North Carolina, March 14, 1825, and is the son of John F. and Sarah W. (Amis) Bryant, who were born in 1790 and 1794, respectively. The father, John F., was the son of Roland and Mary (Hunt) Bryant, and Roland was the son of William Bryant, who was born in Ireland, John F. was a successful farmer, was married in 1814, and was the father of ten children. He died December 6, 1857, and his wife followed him to the grave in 1870. Our subject was reared on a farm and obtained a limited education in the country schools, and followed farming for eight years, in Dallas County, Ark. He then moved to Maury County, Tenn., where he now resides, engaged in farming and stock raising, in which he has been quite successful. He was married, January 4, 1852, to Sarah Hill, a native of Tennessee, born in June, 1828, and the daughter of Isaac and Margaret (Steele) Hill. Isaac Hill was born in North Carolina, in 1800, and died in Marshall County, Tenn., in 1840. To our subject and wife were born eight children: James R., born 1854; Isaac H., born 1856; John F., born 1857; William T., born 1859; Ida R., born 1861; Andrew D., born 1863; Patrick H., born 1866, and Lizzie H., born 1869. Mr. Bryant has given his children a good education and has reason to be proud of them. In 1874 he was engaged in building two miles of railroad, and also built switch and station houses.

Andrew Daly Bryant (1825-1910) of Bryant Station was according to Goodspeed’s History of Maury County…one of Maury County’s most enterprising citizens, was born in Franklin County, North Carolina, March 14, 1825, and is the son of John F. and Sarah W. (Amis) Bryant, who were born in 1790 and 1794, respectively. The father, John F., was the son of Roland and Mary (Hunt) Bryant, and Roland was the son of William Bryant, who was born in Ireland, John F. was a successful farmer, was married in 1814, and was the father of ten children. He died December 6, 1857, and his wife followed him to the grave in 1870. Our subject was reared on a farm and obtained a limited education in the country schools, and followed farming for eight years, in Dallas County, Ark. He then moved to Maury County, Tenn., where he now resides, engaged in farming and stock raising, in which he has been quite successful. He was married, January 4, 1852, to Sarah Hill, a native of Tennessee, born in June, 1828, and the daughter of Isaac and Margaret (Steele) Hill. Isaac Hill was born in North Carolina, in 1800, and died in Marshall County, Tenn., in 1840. To our subject and wife were born eight children: James R., born 1854; Isaac H., born 1856; John F., born 1857; William T., born 1859; Ida R., born 1861; Andrew D., born 1863; Patrick H., born 1866, and Lizzie H., born 1869. Mr. Bryant has given his children a good education and has reason to be proud of them. In 1874 he was engaged in building two miles of railroad, and also built switch and station houses.

In 1877 he engaged in the saw and grist-mill business. He took an active part in the Confederate service during the late war, enlisting in Company H, Fifty-third Regiment, and served two years. He was first lieutenant, and his captain being wounded at Fort Donelson, Mr. Bryant took his place as captain. Our subject was captured and taken to Indianapolis, Johnson’s Island, Camp Chase and at Vicksburg, where he was exchanged. He is an enterprising and successful farmer and stock raiser, and is highly spoken of by his many friends.

In 1877 he engaged in the saw and grist-mill business. He took an active part in the Confederate service during the late war, enlisting in Company H, Fifty-third Regiment, and served two years. He was first lieutenant, and his captain being wounded at Fort Donelson, Mr. Bryant took his place as captain. Our subject was captured and taken to Indianapolis, Johnson’s Island, Camp Chase and at Vicksburg, where he was exchanged. He is an enterprising and successful farmer and stock raiser, and is highly spoken of by his many friends.

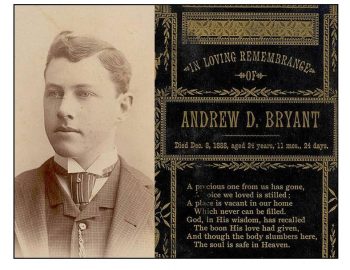

This sketch was written in 1886, two years before the Bryants suffered the tragedy of losing their 24 year-old son Andrew Daly Bryant, Jr. in an accident of some kind in Birmingham, Alabama. The expression on the father’s face in the reunion photograph is one of enduring sorrow.

Andrew Bryant’s cousin Harriet Bryant married James Lewis White’s uncle Archelaus Mays White. They from moved Maury County to a plantation near Madison County, Tennessee and raised the first of several generations of cotton farmers and brokers. Harriet stitched the sampler pictured below which recently was sold by Case Antiques for $11,600.

Sitting next to Andrew Bryant in the reunion picture is his neighbor, James F. Agnew (1839-1922). He lived on 111 acres less than two miles south of the Bryant’s. His grandfather, John Agnew, came from Ireland to Virginia, then to Sumner County in 1802. James was born in Maury County, his father John Jr., being an early settler. James served four years in Company B, 3rd (Clack’s) Tennessee Infantry. He was captured at Fort Donelson, paroled, then recaptured at Jackson, Mississippi. His younger brother, J.M., also a veteran, lived on 95 acres nearby.

Sitting next to Andrew Bryant in the reunion picture is his neighbor, James F. Agnew (1839-1922). He lived on 111 acres less than two miles south of the Bryant’s. His grandfather, John Agnew, came from Ireland to Virginia, then to Sumner County in 1802. James was born in Maury County, his father John Jr., being an early settler. James served four years in Company B, 3rd (Clack’s) Tennessee Infantry. He was captured at Fort Donelson, paroled, then recaptured at Jackson, Mississippi. His younger brother, J.M., also a veteran, lived on 95 acres nearby.

Also serving in the 3rd Infantry, in Company E, was James Anderson Vincent (1840-1933) of Mooresville. His father was from North Carolina and his mother was from Virginia. Before the war, his widowed mother claimed she had more than $21,000 in personal property and $8,000 in real estate which made them the most prosperous of their nearby neighbors. After the war in 1870, she still valued the property at $8,000 but she claimed $1,000 in personal property. James Anderson, his wife, and infant lived next door. By 1902, James was widowed, living with his spinster daughter and a servant and seems to have achieved a measure of prosperity.

Also serving in the 3rd Infantry, in Company E, was James Anderson Vincent (1840-1933) of Mooresville. His father was from North Carolina and his mother was from Virginia. Before the war, his widowed mother claimed she had more than $21,000 in personal property and $8,000 in real estate which made them the most prosperous of their nearby neighbors. After the war in 1870, she still valued the property at $8,000 but she claimed $1,000 in personal property. James Anderson, his wife, and infant lived next door. By 1902, James was widowed, living with his spinster daughter and a servant and seems to have achieved a measure of prosperity.

William Henry Watson (1845-1913) joined Company K of the 48th Tennessee Infantry, then Company G of the 9th Tennessee Cavalry. He was the son of Alexander Watson (1803 – 1875?) who came from England as an orphan boy without family. He came to Maury County some time before 1840 and eventually owned 210 acres in Culleoka. He married Patsy Jones who bore him six children.

William Henry Watson (1845-1913) joined Company K of the 48th Tennessee Infantry, then Company G of the 9th Tennessee Cavalry. He was the son of Alexander Watson (1803 – 1875?) who came from England as an orphan boy without family. He came to Maury County some time before 1840 and eventually owned 210 acres in Culleoka. He married Patsy Jones who bore him six children.

Maple Watson Tindell (W.H.’s daughter) said this about the family:

Grandpa [Alexander] was afflicted with crippling rheumatism for twenty years in wheel chair before he died. Granny Patsy had a hard time providing for her flock, often knitting socks under the bed clothes when firewood was scarce…They owned their home and stock for tilling the ground and cows and hogs for milk and meat.

During the war, while W. H. was away fighting, Union soldiers pillaged Alexander’s farm, took all his stock, and shot his only milk cow in his front yard. They took the hind quarters and left the rest. He never recovered financially from the war. At his death, he owed $400 – which W. H. paid off.

According to his obituary, William H. Watson was considered by his fellow veterans as “one of the bravest who wore the gray” and was “universally esteemed” by them. He was a member of Forrest’s “old brigade,” consisting of the 4th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th Tennessee Cavalries. This was considered by many as “the finest body of cavalry in the western army.”

Early in the war, he along with three of his boyhood friends (John and James Patterson, and Jim Craig), came down with typhoid fever right before the Fort Donelson debacle — likely they would have been captured otherwise. He was sick for several weeks then recovered, never to be excused from active service for the balance of the war, except for “a day and a half in the Chickamauga campaign…from overeating raw potatoes and raw pork.” He was wounded at Mossy Creek but kept fighting. He was never a prisoner.

He once told a writer about an incident during the fight at Dibbrell’s Ridge near Dandridge, Tennessee in late January, 1864. General W. T. Martin had ordered an ill-advised retreat while General G. G. Dibbrell of the 8th Cavalry turned the tide of battle by taking a strong position against a range of hills, blocking the enemy’s pursuit.

“…we received them with a yell and a shout that drove them back in great confusion,” said Dibbrell.

“…General Elliot retreated thirty-five miles before stopping and citizens reported his loss at 350 killed and wounded. He reported at Sevierville he had fought all of Longstreet’s Infantry. Our loss was two killed, five wounded, and three captured.”

During the fallback, three columns of Yankees quickly advanced and W. H. and his comrades hastily made a breastworks of a rotten log. When the Union soldiers fired, the Minnie balls ripped right through the log wounding seven men. Among them, Henry Payne’s right arm was shot off and Henry Cox’s face was disfigured by the rotten splinters. “He was a heap less better looking after that,” remembered W. H.

Like most of his comrades, Watson returned home after the war penniless but he worked at lumbering, logging, and rafting and, in time, became a very prosperous “stockman and trader.” In his old age, he moved to town and established a “livery stable, sales and hitch barn” at the bottom of the hill, at the east corner of 8th Street and South Main in Columbia.

Up the block at 9th Street, there was a wholesale grocery and tavern “for colored people” ran by a man named Lazarus. Maple Watson Tindall remembered “…[an] old blind black woman who played the accordion and sang songs that were old even then…She also had a tin cup for donations. A very colorful place.”

Many of his country friends would come into town to visit him and W. H. would always invite them for lunch. W. H.’s wife, Ellen Journey Watson (with whom he sired six boys and six girls), died when Maple, the youngest child, was six. Maple quit school at 15 to keep house for her father:

…So we lived with open house, I never felt I was imposed on because of the extra cooking and work. I was so gregarious that I enjoyed hostessing all comers. My daddy never liked oil cloth or any make shift tablecloth, nothing would do but white linen.

…When my mother lived we always went to Baptist Sunday School and Church, and to their picnics and socials. After she was gone, Pappy and I would shop around for religion, we always made a nice contribution. To contribute was a point of honor with him to always pay his way. Well, the outcome of this shopping around was that we were uncertain which sort of faith to embrace. They differed in detail so much that he never could decide. Once an old man prayed for ever so many things. On our way home, Pappy said, “He ought not to bother the Old Master that way, because he could gotten most of that for himself”. He was devout and on Sunday afternoons he would have me read aloud from the Good Book.

A good friend of W. H. Watson was fellow cavalryman, James M. “Jim” Gilliam (1842-1903). His grandfather, the Virginian Thomas Gilliam (1778-1844), came to Tennessee in 1806, settling in the Rock Springs Community of Maury County two years later. In 1812, he built the Wallace Mill, the first mill established on Duck River.

A good friend of W. H. Watson was fellow cavalryman, James M. “Jim” Gilliam (1842-1903). His grandfather, the Virginian Thomas Gilliam (1778-1844), came to Tennessee in 1806, settling in the Rock Springs Community of Maury County two years later. In 1812, he built the Wallace Mill, the first mill established on Duck River.

Jim Gilliam was a member of Company F, the 1st Tennessee Cavalry. Historian Frank H. Smith tells a story about Jim and W. H. Watson in his book, The History of Maury Co., Tennessee:

[In the Spring of 1863] while the troops of N. B. Forrest were harassing the Federal forces in Middle Tennessee, some of the soldiers, including W. H. Watson and Jim Gilliam, “just straggled and became ‘buttermilk rangers.’”

They went to Lickskillet (Gilliam’s home) and the next day started toward Spring Hill to join their comrades. As they were riding down a ravine near Bear Creek Pike, they rode into the middle of a detachment of Federal troops concealed behind a fence. The Yankees discovered the Rebel soldiers and tried to stop them.

In the skirmish, Gilliam’s horse was shot though the neck and fell on top of its rider. The others stopped and “began firing with pistols, and the whole Federal line broke. A moment or two afterwards, John Caldwell (civilian?) came riding down the road to see what was going on. He was well mounted.

Watson drew his pistol on John and made him give his horse, saddle, and bridle to Gilliam. Caldwell took Gilliam’s equipments and wounded horse.

Seven or eight months later, on another raid through here by Forrest, Gilliam and Watson went to see John Caldwell. Caldwell had doctored the Gilliam horse, and Gilliam “swapped horses” again with Caldwell, leaving Caldwell his original horse, much the worse for wear. Gilliam claimed that he was such attached to his (original) black horse as he had captured it from a Yankee colonel in battle. Nobody was wounded in this affair between the three scouts and two companies.

Jim Gilliam married Nancy Jane Denham, the sister of his fellow 1st Tennessee cavalryman Andy Denham. Jim’s son George married Elizabeth America Davidson, the niece of John and William Davidson, and also the niece of my great-grandmother Ophelia Tennessee Davidson White (wife of James Lewis White, 1st Tennessee Cavalry, CSA).

Jim’s nephew Thaddeus Nathaniel “Thad” Gilliam married Margaret E. “Mag” White, daughter of James Lewis White. So, as you can see, the men in the reunion photograph were connected by more than war and geography. As could be expected of small communities, companies of volunteer soldiers were often made up of brothers, cousins, in-laws, and other kin.

Jim Gilliam’s brother-in-law, Andrew Elijah “Andy” Denham (1845-1931) of Company F, the 1st Tennessee Cavalry, was the grandson of Robert Forgason Denham who came to Maury County before 1820 (probably from South Carolina). He purchased property on Silver Creek in 1824. Andy’s father Samuel died in 1847 when Andy was less than 2 years old.

Jim Gilliam’s brother-in-law, Andrew Elijah “Andy” Denham (1845-1931) of Company F, the 1st Tennessee Cavalry, was the grandson of Robert Forgason Denham who came to Maury County before 1820 (probably from South Carolina). He purchased property on Silver Creek in 1824. Andy’s father Samuel died in 1847 when Andy was less than 2 years old.  His four siblings ranged from infancy to five years old, all to be raised by their 25 year-old mother Lydia Pinkston Denham. She married Edward Cooper in 1856. The “old Denham homestead” was described as being 355 acres, 11 miles from Columbia near the Lewisburg Road…a desirable property with 100 acres under cultivation and the rest partly timbered with oak, ash, and cedar, some of the larger trees having been removed.”

His four siblings ranged from infancy to five years old, all to be raised by their 25 year-old mother Lydia Pinkston Denham. She married Edward Cooper in 1856. The “old Denham homestead” was described as being 355 acres, 11 miles from Columbia near the Lewisburg Road…a desirable property with 100 acres under cultivation and the rest partly timbered with oak, ash, and cedar, some of the larger trees having been removed.”

Shortly after the war, Andy moved to Rutherford County, where in 1871 he married Martha Reeves and raised a family. The Dallas convention no doubt reunited him with boyhood friends he had not seen in 30 years.

Andy Denham’s brother-in-law, Newton Granville Cockrill (1833-1915) had been married twice before he married Andy’s sister Mary Matilda. His first wife Mary Box died in 1854, his second wife Mary Freeland passed away five days before the war ended in June of 1865. Newt married Mary Matilda six months later. She bore him four children and outlived him by nine years.

Andy Denham’s brother-in-law, Newton Granville Cockrill (1833-1915) had been married twice before he married Andy’s sister Mary Matilda. His first wife Mary Box died in 1854, his second wife Mary Freeland passed away five days before the war ended in June of 1865. Newt married Mary Matilda six months later. She bore him four children and outlived him by nine years.

Newt was the grandson of Lewis Cockrill, a Virginian, who came to Maury County some time before 1840. Newt served in Company F, of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry. He was never wounded nor a prisoner. After the war, he farmed on Fountain Creek.

Fountain Creek is the settlement George Davidson came to from Virginia around 1806 to establish a farm. He was the grandfather of William A. “Bill” Davidson (1838-1923) and John Davidson (1833-1934), brothers-in-law to James Lewis White who married their sister Ophelia Tennessee Davidson. Both served in Company K of the 48th Tennessee Infantry.

Fountain Creek is the settlement George Davidson came to from Virginia around 1806 to establish a farm. He was the grandfather of William A. “Bill” Davidson (1838-1923) and John Davidson (1833-1934), brothers-in-law to James Lewis White who married their sister Ophelia Tennessee Davidson. Both served in Company K of the 48th Tennessee Infantry.

Major Gerald Kincaid has written a fine book about the 48th. Here are two excerpts that make salient points about the regiment:

The 48th was in many ways a typical Tennessee regiment; quickly recruited, untrained, poorly equipped, and hastily ordered into Confederate service. The majority of the men who formed the 48th were from the prosperous and very secessionist middle Tennessee counties of Hickman (1807), Maury (1807), Lewis (1843), and Lawrence (1817). The State formed these counties in 1817 due to a large migration of settlers of Celtic and English descent from North Carolina.”

The raw recruits mustered in at varied locations but most notably in the towns of Columbia, Waynesboro, and Lawrenceburg…

The 48th, unique in the annals of Confederate military history, was broken on the anvil of defeat at Fort Donelson and reforged into two separate effective regiments. These twin regiments then fought in varied locations as two separate yet connected regiments for twenty-seven months. The distinction of being separate organizations enabled the 48th to list battle credits unlike any other regiment during the war.

An early test was the disaster at Fort Donelson in January of 1862 where 270 soldiers were taken prisoner. My great-grandfather was in the 48th at this time and was one of the approximately 250 who escaped.

Enlisted men were taken to Camp Douglas where disease and starvation killed 45 of this number in nine months before a parole was negotiated. Not everyone was in favor of parole, as noted by Major Kincaid:

One Federal Officer thought the exchange was a mistake. Campbell reports the officer said “all the weakly prisoners had died, the cowardly had taken the oath, and the others would make invincible soldiers”…

…By the time the 48th was organized, the reality of the war was apparent, and Union troops were encroaching on Tennessee. The 48th’s recruits were not the nonchalant lads of early 1861 who rushed off to engage in a short, romantic war. The days of the ninety-day enlistment were over, and the men enlisted in the 48th for a least a year. Those who served in the 48th were true volunteers; the draft would not be an inducement to enlist until April of 1862.

The 48th rarely contained over 500 men, but nearly 1,850 men served in the regiment at one time or another. Less than sixty men who enlisted in 1861 were still fighting with the 48th when the final surrender of the army took place at Greensboro, North Carolina. Despite the regiment’s participation in a number of battles, it was disease, desertion, and capture that continually whittled down their numbers.

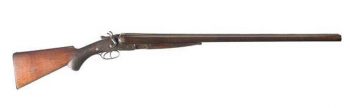

My father owns a fine English-made shotgun, a 16 gauge William Moore side by side, owned by the Davidsons and handed down through my grandfather Robert Taylor White. I suspect it was a Civil War firearm supplied the South by the British. Nevertheless, it was a favorite squirrel gun of my 91 year-old dad when he was a boy.

William Davidson returned home from the war and married Margaret Crunk. They had ten children. John, who nearly lived to be 100, never married and lived with William and his family.

J.N. Meroney (1843-1918) Sergeant, Company E, the 19th Tennessee Infantry, was the great-nephew of General John B. Hood. He was wounded at the Battle of Franklin.

J.N. Meroney (1843-1918) Sergeant, Company E, the 19th Tennessee Infantry, was the great-nephew of General John B. Hood. He was wounded at the Battle of Franklin.

After the war, Meroney lived at Dark Station, about 6 miles north of Columbia. There he was postmaster and historian for the Lasting Hope Cumberland Presbyterian Church, near the former plantation lands of Colonel W. M. Voorhies and Captain George W. Gordon of the 48th Tennessee.

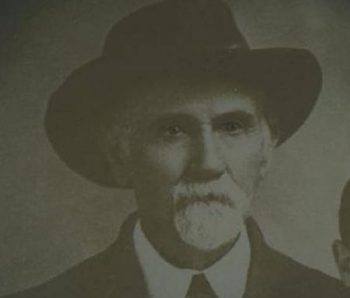

Missing from the reunion photograph and the occasion itself is a veteran of the 48th, my great-grandfather James Lewis White (1842-1919). Why he wasn’t present is a mystery.

James Lewis White was the grandson of Lewis and Nancy Mays White, Virginians who came to Maury County in the early 1830s. Twenty years later, the widower Lewis moved to Madison County with three sons, Archelous, James, and John, who became prosperous cotton planters. He left behind his eldest son William, William’s wife Margaret Covey, and their young family which included James Lewis.

According to Goodspeed, James Lewis White “was reared on the farm and received his education in the common schools.” In 1861 he enlisted in Captain Howlett’s Company F, 48th Infantry and was captured at the battle of Fort Donelson in 1862, then escaped.

He then joined Company F, 1rst Tennessee Cavalry and fought in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina before surrendering at Charlotte, North Carolina May 3, 1865. He was paroled in Charlotte and family legend has it that he walked the entire 500 miles home to his farm. In addition to farming, in 1878 he was elected constable and served 4 years. In 1882 he was elected magistrate as a Democrat and was holding that office at the time of Goodspeed’s publication in 1887.

In his obituary, entitled “Prominent Official Summoned by Death,” it says that James Lewis was a “former deputy sheriff and served as a member of the county court for many years collecting accounts.” The article states that he was considered the best in the county as a collector, and had held public office for 38 years as a deputy under sheriffs Webb, Forgey, and Godwin. He was a “most capable and highly esteemed officer.”

In his old age he suffered with crippling arthritis which exasperated his already fiery and cantankerous nature.

James Lewis White is buried at Morton Cemetery near Gene Cheek’s farm, as is his son Willis.

Ophelia, his wife, is buried elsewhere — at Haynes Cemetery. She always said that she didn’t want to be buried at Morton’s because it was near Duck River and she feared the cemetery would flood. However, I personally speculate that a lifetime with James Lewis White was plenty for her.

Three of my ancestor’s companions have not been identified:

Perhaps one day old photographs and hand-scribbled records from someone else’s forgotten file will bring their stories to light. I hope so. I am certain there will be interesting tales to tell.

Among the ones we do know about, there is a common denominator that fascinates me – their longevity!

The life expectancy for a male in 1902 was 49.8 years. The average age lifespan for these gentlemen was 87 years – 61 being the youngest, and 99 the oldest.

Considering all they endured prior to, throughout, and following the Civil War, the only conclusion one can reach is, they were extraordinary men. Studying their faces through the years, I always suspected as much.

I am very glad to know their stories. I am grateful to my friends Tom and Dot Gilliam for leaving a well-marked trail to follow.

Update May 15, 2024 —

Two of the three previously unidentified veterans are profiled below:

Captain Isaac James Howlett (1839-1922) The aforementioned Captain Howlett, under whom my great-grandfather served, was profiled in Goodspeed’s History of Maury County in 1887 —

“Captain Isaac J. Howlett, merchant, of Culleoka, was born in Davidson County, April 4, 1839, the son of Addison B. and Elizabeth (Clemmons) Howlett. Addison Howlett is of Scotch parentage, and is a prominent farmer of Davidson County, where he yet lives. The mother died in 1872. Isaac J. secured a fair education, and in 1835 began earning his own living by clerking with an uncle, S.B. Howlett in Mooresville, with whom he remained until 1861. He then enlisted in the Confederate Army, and was captain of Company F, Forty-Eighth Tennessee Infantry. He was captured at the fall of Fort Donelson, and was imprisoned at Columbus and Sandusky, Ohio. After his return home, he farmed for about a year and a half and in 1868 went to Gadsden, Tenn., where he engaged in merchandising in partnership with William Linder. In March, 1871, he sold his interest and returned to Maury County, and collected for his uncle until December, 1879. He then came into possession of the store by his uncle’s will, and has since carried on the business very successfully. He owns fifty acres of land and his business house and residence property. March 28, 1861, he married Mary R. Howard and they have six children: Kirby S. (a physician of the county), Mary I., Jenny L. and Lizzie (twins), Minnie M., and Adah. B. Mr. Howlett is a Democrat and the family are Presbyterians.”

By 1900, Captain Howlett had moved to Nashville where he was first involved in the grocery business, then served as a deputy in the County Register’s Office until near time of his death. Interestingly, he was a member the Frank Cheathan Bivouac and Camp and served on a committee to organize transportation to the 1907 Confederate Reunion in Richmond, Virginia.

He died in Nashville at 82 years old, and his body was returned to Culleoka to be buried at Wilkes Cemetry.

William M. Richardson (1840-1913), a private in Company E, of the 48th Tennessee Infantry, was the maker of the famous Richardson Saddle. His obituary reads that he “was born in the Culleoka section and lived there all of his life…For four years he was a gallant and faithful soldier of the Confederacy. He never shirked a duty. After the war he engaged in the making of saddles and his product soon came to be known for their absolute honesty and superior quality of the workmanship bestowed upon them.”

Kevin Rogers writes, “While in the Confederate Army during the Civil War he vowed that when he got home that he would make a saddle that was comfortable to the rider and would not rub sores on the horse. This he did.

People came from far and near to be fitted, both rider and horse, for one of Richardson’s creations. While he made various styles all had similar features – up-curved pommel and cantle, scalloped edging, lacing, decorative brass dots, broad leather sides and wide wood stirrups. Every saddle exuded with evidence of craftsmanship. Satisfied customers said that ‘they fit like a glove.’

“Upon the death of William M. Richardson, his son William L. Richardson continued his father’s saddle business from his shoe and leather shop in Mt. Pleasant, Tennessee until his sudden death in 1946. Later the patent for the Richardson saddle was bought by The Tennessee Harness Company.”

The obituary went on to mention that he had been a very successful farmer, that he had been married to Lucy Jane Tate for 37 years, and they had raised ten children. Two predeceased him and several had moved to Texas by the time of his death.

The writer also noted that Richardson was “a devoted member of the Methodist Church, a faithful attendant at Sunday school, charitable, public spirited, always a friend of the sick and distressed,…one of the best citizens of the community. No man in all that section was more prompt to visit the homes where there was sickness or want. He was especially attentive to the aged and the infirm. Honest, truthful, a good neighbor, a sincere Christian, his loss will be universally mourned by the community.”

His memberships in the Masons and Confederate organizations also were noted.

He died in his sleep at age 72.