Mr. Kinnie Polk “Sam” Freeland and Miss Ida had a boy born to them more than a dozen years after their last one, Tom (named after the bachelor uncle who lived with them in the big old house in Scribner Mill).

Jack was the blessed infant’s name and, from the beginning, he was doted on and seldom corrected by Miss Ida. His uncle Thomas who lived in one end of the big old house was particularly amused by the boy and would laugh at his every utterance.

That’s one reason that, by the time he started first grade, Jack cursed worse than any sailor.

Miss Ida of course was worried about Jack’s academic career so she walked across the hill separating the Freeland farm from the White farm to talk to my dad (also named Jack, and possibly the other Jack’s namesake). Jack White was then in the seventh grade at Bryant Station School and had proven himself to be a good, reliable Christian boy.

Miss Ida said, “Jack, I’m layin’ it on you to take care of Jack Freeland when he starts school.”

“Oh, Miss Ida…” my dad protested.

“No. You take care of him,” Miss Ida retorted. Then she turned and walked back to her house.

Well, my dad thought so much of Miss Ida…she cooked pies and such for him occasionally and was always sweet to him, and he thought the world of her brother-in-law Thomas who cut his hair and worked in the fields with him and was just like an uncle to him…

It was a responsibility of great weight but because of Miss Ida he was resolved to bear it.

By the way, Jack Freeland was not the only foul-mouthed youngster to start first grade during that time. Across the way from Bryant’s Station, Jack’s school, was Fountain Heights. There, Billy Spivey was attending his first day of school.

A new teacher had been hired and she was going down the row of mothers and first graders introducing herself, all the while making light conversation and trying to make a good impression. When she came to Billy Spivey, she said, “What’s your name young man?”

“Billy Spivey,” said Billy.

“So, Billy, do you know your ABCs?”

“H@#$% no! I’ve only been here, 10 minutes!”

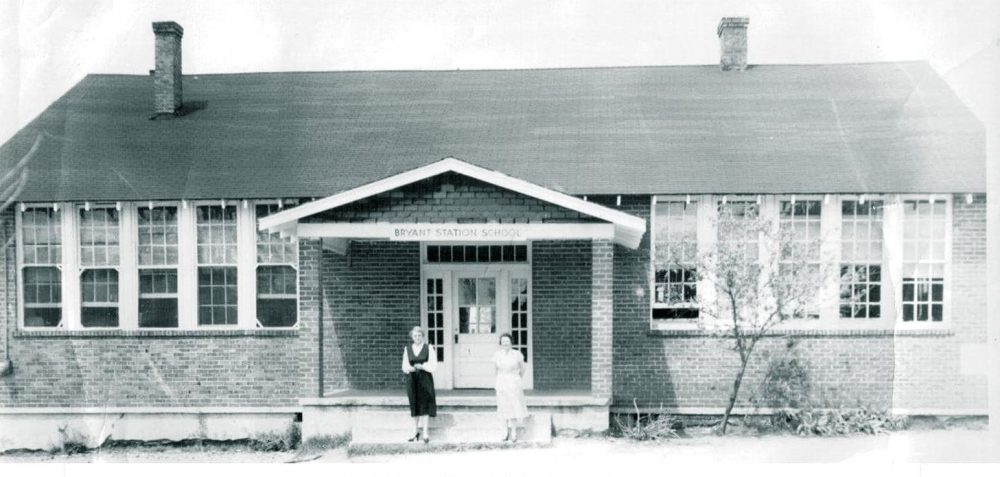

Nonetheless, Jack Freeland and Jack White, along with a passel of other kids walked the mile and a half or so from Scribner Mill to Bryant Station to begin the 1934-35 school year.

When they arrived at the two-room school house, Jack left his charge with the teacher for grades 1 through 4, then crossed the hall to Mr. Bill Orr’s room for grades 5 through 8.

At recess, Jack White surveyed the playground for his young ward — to no effect! Jack Freeland had made a jail break!

Frantically, my dad ran from the school down the trail back home. About the county highway, a mile away, he caught up with Jack Freeland.

“Jack, you turn around and come back to school!” commanded my dad.

This released a truckload of oaths, epithets, and terrible language like Jack White had never heard. Finally, the profanity was ended with a proclamation.

“I ain’t going back to that !@#$% school and there ain’t no !@#$% can ever think about makin’ me! And, while you’re at it, you can go to straight to !@#$%!!!”

My dad looked at Jack.

“Miss Ida told me I was to look out for you, and if you don’t turn around and go back to school, I’m gonna take off my belt and give you the thrashing of your life!”

Jack Freeland looked at my dad.

“You ain’t gonna do that.”

“Try me,” said Jack White.

So Jack Freeland returned to school. And, from then on, whenever he would start to act up, all my dad had to do was to give him a stern look and he would straighten up.

My dad recollected this over coffee this morning, eighty-four years after the fact. He smiled when he remembered.

“…And, you know, by the time he was in the third grade, he didn’t cuss near as bad.”