From the age of ten, my dad worked a brace of mules named Matt and Dinah.

“My dad would stay in the field and watch me to make sure I was safe but he turned me loose with them by the time I was twelve or thirteen.”

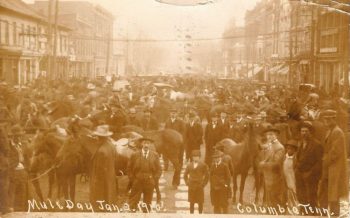

My grandfather Bob White bought them in 1933 at the jockey yard off the courthouse square in Columbia. This is the lot at the corner of East 7th and Woodland Street, behind what are now the offices of the Maury County Clerk but once was the site of the Park Seed Company and Hop’s Cafe.

The mules were a solid white matching team, powerful and impeccably turned out except for Dinah’s right ear which was stiff and pointed straight up to Glory.

When the family got Matt and Dinah back to the farm, they stabled them in adjoining stalls and left them for the evening.

“In the morning,” said Jack, “I walked into the hall of the barn to discover they had kicked in the partitioning wall and were standing side-by-side in the brand new, big stall as calm and unconcerned as if they’d just performed minor housekeeping.”

When Jack let them out to water, they casually sauntered to the spring running through the barn lot.

“There was an iron pipe running from the rocks and spring on the hillside beside the barn. Those mules, as peacefully as you please, walked over and started drinking directly from the pipe.

“The other thing they would do, and they started that morning, they would return from the spring, then back into their respective places of whatever you were preparing, be it wagon or plow. They would wait patiently for you to gear them up – Dinah on the Gee side and Matt on the Haw.” From this ritual, they never waivered.

“You know, an animal is more intelligent than a human being on occasion,” my dad said. “For one, they can sense the danger of things.”

He then went on to tell the story of a much-less-beloved mule named Doc, who was bad to plow a crooked row. Additionally, he developed a certain trick for self-amusement where he would hunker down his rump below a cultivator and flip it over – which was embarrassing for a thirteen year old, because Jack would have to seek help turning it upright.

“Well, how did that happen?” the adult would ask. And Jack would have to explain it, and the grownup would stand there looking at Jack like he was an imbecile.

One day, Jack was plowing some ground with Doc while his Uncle Willis, a Columbia policeman, smoked a cigarette and observed from a rail fence.

After watching the struggle between boy and beast for awhile, Willis called out to his nephew.

“Jake! Let me have ol’ Doc a round or two.”

He climbed over the fence in his police uniform and shoes and took the line from Jack. He then proceeded to plow.

Doc was no respecter of anyone, even an officer of the law, so he immediately went into every rebellious and independent routine he could conjure.

Willis calmly took it all in for about a half a row, then threw out his check line in a big long loop like he was casting for trout, before popping it down hard like a hammer on Doc’s back!

“WHACK! You could hear that line pop a mile away. Hair flew off Doc’s back high as a flagpole!”

“Haw,” Willis calmly commanded, and Doc made a perfect left turn with no argument.

Willis plowed another row or two before handing back the lines to Jack.

“I don’t think he’ll trouble you,” said Willis.

“And, from there on out, he did everything I called on him to do,” said Jack.

But one day, Jack was plowing a tobacco patch with one corner near a groundhog hole.

“Every time, I would pass the groundhog hole, old Doc would break into his old ways. He’d shy away from the hole and make a mess of my row. The harder I struggled, the more he veered.”

Later that winter, about a five foot circle of ground collapsed around the hole, leaving the sod totally undisturbed like a blanket.

“It was like a man took a saw and cut a perfect circle.”

The groundhog hole was the center of a very deep sink hole.

My dad told an elderly neighbor about it, and the old man said, “I know that ground.”

He told about coon hunting there forty years before and while he was listening to his dog bark on the trail, suddenly, the sound shut off like a light switch.

“After a while, I heard a weak howl from very far away. So I started walking toward the sound.

“Luckily, I had my torch or I would have stepped into a big old sink hole!

“I shined the light down the hole and I could see my dog on a shelf about ten feet down, but past him I never saw bottom.

“I had to go home and get a long ladder to get him out.”

Over the many years that followed, the surface crater filled in, leaving a small opening that resembled a groundhog hole.

“So,” my dad said, “Doc sensed that hollow ground. He knew there was danger there. And I just thought he was being contrary.”

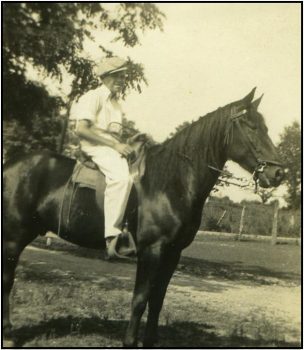

Red Top mule farm, Midlothian, Texas, owned by D. Frank Gibson, my great-grandmother’s second husband.

There can be no doubt Matt and Dinah were two highly intelligent animals. Additionally, they were a very close and devoted couple.

Once, and for the first and only time, Bob took only one mule, Matt, to plow a tobacco patch on top of a high hill about a mile away from the barn. While he was plowing, Dinah kicked out of the stall and out the barn door.

She then tracked Bob and Matt down a trail to the garden spot on the other side of the farm.

Bob was walking along, plowing one of his long, straight rows for which he was known, when he heard a snort. He turned to see Dinah serenely and contentedly following close behind.

“If you knew my daddy, you know he nearly jumped over those plow handles when he saw that white mule.”

“I don’t know why, but he was a wary man. He walked with an open pocket knife in his pocket the whole time I knew him. You would hear the knife click shut when he got home.

“It was funny. He was, for the most part, brave but there were certain things that scared him. He was afraid of birds. If a chimney sweep flew into the house through the fireplace and got to flying around, he would run out the door until someone caught the bird. And he wouldn’t return until the bird was freed outside.

“Why, you could run him all over the country with a bird.”

From the time of the trailing mule forward, if Bob was just working one mule, he’d take the other one with him and tie the idle mule to a tree. The mule would wait until the work was done, just as satisfied as could be.

Columbia, Tennessee is the Mule Capital of the World and, in a time when hardly anyone had a tractor, a farmer took great pride in his mules. I still have the hand clippers Jack used to groom Matt and Dinah.

“Esman Howard was the only neighbor I can remember who had a tractor,” said Jack. This was in the 1920s and ‘30s.

“It had iron cleats instead of rubber tires. Once he got hung up on a big rock and sparks and flames were shooting out from under those cleats until I thought he was going to set the county on fire.”

Matt and Dinah not only were a handsome couple, they were extraordinarily powerful. Two stories illustrate this.

The County used to pay crews to dig and load sand from sand bars in the creeks around Columbia — $3.00 per day for wagon and team, $1.75 per day for the driver, and $1.25 per day for the fellows working the shovels. The sand was used for the rural roads before the days of crushed rock, then asphalt.

One day Jack and his brother Tom hired out to haul sand out of Fountain Creek near Scribner Mill. They brought Matt and Dinah to pull their wagon with a dump gate, Tom to drive, and Jack for the shovel crew.

At the hauling point, there was a high hill to pull out of the creek. Unbeknownst to Jack, his fellow shovelers began betting on whether or not the white mules could pull the hill with a wagon loaded down with sand. To help their cause, the men who bet against the mules would furtively shovel in front of the wagon wheels when the others weren’t looking. The wagon was parked in the creek so the wheels were partially submerged and the ploy went undetected. So, not only did the mules have to pull the hill, by the time the wagon was loaded, they had big creek wallows to pull out of besides.

Again, my dad was totally unaware of what was going on until Matt and Dinah pulled the wagon through the creek, up the high hill, and out of sight without breaking a noticeable sweat.

“Them mules of yours just cost me a week’s wages,” said a shovel man standing next to my dad.

It was then the wager was revealed.

“Another time, two black gentlemen from Centerville came to the farm in an old truck. They were driving through the country buying scrap iron,” said my dad.

After they were loaded down, they left to navigate the narrow dirt road leading from the farm.

About an hour later, they returned on foot. They knocked on the door and Bob answered.

“Mister, do you have a tractor,” the man inquired.

“No. I have a team of mules,” said Bob.

“I don’t believe those mules can help us. We’ve run off the road with that heavy load of scrap iron.”

“You won’t begrudge a man for trying will you?” asked Bob.

It was after dark and my grandparents didn’t have a telephone back then so the man’s options were limited. The scrap iron men walked back to their truck and awaited Bob and the mules.

After awhile, my grandfather arrived with Matt and Dinah. The two men sat by their truck which tilted sideways in a ditch. The back wheels were half-buried in the soft earth. The men wore sad looks of tired resignation.

Then the man who had spoken to Bob on the porch looked up to see the mules. His eyes opened wide as if in great surprise and recognition.

“Those mules will pull me out,” he said. Then he stood up, approached the mules, and crooked his finger through Dinah’s bit strap. He gently rubbed her face and touched the stiff ear.

“I broke these mules, Mister. I know they can do the job.”

And sure enough, Bob hitched a chain to the truck and the mules pulled it through the mud and back onto the road with no problem.

Afterward, the man revealed how Dinah got the stiff ear.

“I was riding a wagon the mules were pulling and a cousin of mine was driving. As we passed under a hickory tree, I reached up and grabbed a green hickory nut. I said to my cousin, watch me thump this nut into that mule’s ear.

“Well, I thumped it never thinking it would hit the target, and it shot right down that animal’s ear.

“And that mule had a fit. She reared up and she kicked up and she side-winded, and she started rodeoing with us going downhill in that wagon. It’s a wonder we didn’t get killed.

“And that’s how she got that ear.”

Many years later, my dad had a fishing camp in Linden, Tennessee and, as my mother and he passed through Centerville, he stopped her off at a beauty shop where she could get her hair done. While he was killing time, he wandered over to the Hickman County Courthouse, just to walk through it and look around.

Much to his great surprise, on the wall in the courthouse was an old photograph of Matt and Dinah hitched to a plow, with an inscription that read something to the effect, “Two fine examples of Hickman County mules, purchased by a farmer at the jockey yard in Columbia, Tennessee.”

Jack was proud to know his two old friends were still appreciated in their home community.