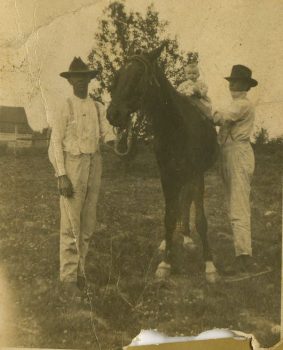

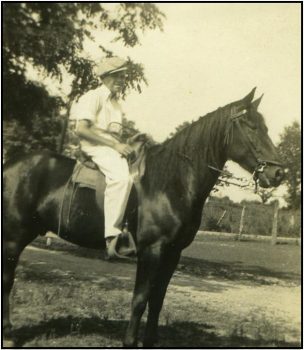

Lauriston “Laurice” Mayberry was an old man who lived on Silver Creek and rode a little black Walking Horse to Galbreath’s Store. He was the grandson of Revolutionary War soldier Henry Mayberry who came to Tennessee from Virginia in the late 1790s.

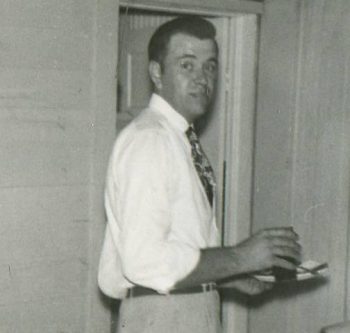

Both Laurice and his son Hardin took a great liking to my dad’s cousin and best friend Douglas White. In 1934, Doug was a goodlooking cotton-headed boy of 11, with a great personality, who already was a fine horseman.

Tom, Kathryn, Jack, Douglas, and Ann Louise White. Tom, Kathryn, and Jack were siblings. Doug and Ann Louise were their cousins.

It was Hardin who had the idea of entering Doug and Laurice’s horse in all the area Walking Horse shows.

My dad said, “Doug was a good rider but that little black horse had more sense than any animal I ever saw.

“The announcer would say, ‘Flat walk, please…’ and as soon as ‘please’ left his lips, that horse would go into a flat walk — before Doug ever gave a command. The same on a running walk, canter, whatever the fellow announced.

“All Doug had to do was stay in the saddle and smile. Of course, a goodlooking kid on that black horse…he won every show he ever rode in.”

Doug’s dad was Fred, brother of my grandad Bob. They were as close as Doug and Jack and lived on adjoining farms.

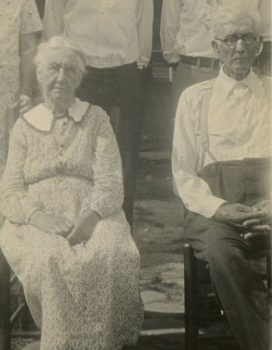

Bob and his family lived with and took care of his parents — the Civil War cavalryman James Lewis White and his wife Ophelia Tennessee Davidson. Fred lived in the big house on the hill built by James Lewis’s brother John. Fred, his wife Mary and two children lived with Uncle John and Aunt Ann and looked after them in their old age, eventually inheriting the property after their deaths.

Life was hard in the country during the 1920s and 30s and the boys worked young in the fields but they still had time for play and good times. Jack and Doug built a “fishing camp” out of metal road signs Fred picked up from working with the county. They would fish on Silver Creek and catch buckets of small, bony, but tasty sun perch.

Uncle John was 85 years old and would be out there every good day, sitting in a cane chair off to himself fishing. He kept a sharp pocket knife he cleaned the fish with and Mary would cook them for him.

He was tolerant of the boys but never had much to say to them. In the evening, they would swing in the swing on the big front porch and he would sit by the front door in his rocking chair, keeping time with his rocking by tapping the arm rest with his knife. We still have that old chair with the deep crater in the wood from his knife.

I say Uncle John was tolerant of the boys because when Jack and Doug weren’t riding horses, they were riding goats and that kind of activity builds up a pretty strong aroma by the end of a warm day.

Very tragically, Doug had been sickly for a spell and was diagnosed as having diabetes. In 1935, doctors couldn’t do much to treat the disease, and in late November, nine days shy of his thirteenth birthday, Douglas died.

At twelve years old, my dad lost his best friend.

Of course, this event devastated Fred and Mary, not to mention other family members and friends. Hardin Mayberry was particularly upset. He was a big, stout fellow, 46 years old, but he died of a heart attack soon after Doug. Laurice was 76 at the time and lived another eight years.

Another odd and cruel effect of Doug’s death, was afterwards Fred slowly developed a coldness and a kind of resentment toward Jack. Who could say what the psychology was behind it but the facts were the Good Lord had claimed Fred’s fine-looking, promising young son, and here was Bob’s boy still alive and healthy.

Fred had always loved Jack, who he called “Jake.” He joked and carried on with him all the while Doug was alive but now he hardly spoke to him.

Probably what exacerbated this was, before Hardin Mayberry died, he gave Jack a horse to train for the horse shows. Yet the horse never even made it to a show.

“His back legs were too straight,” said my dad. “I could tell when I first saw him, he’d never make a Walking Horse.”

It was probably tough for Fred to see a young boy riding a horse — any young boy.

A few years after Hardin died, my dad made a deal with his widow to milk her cows and sharecrop. They would split the milk check and she would get one third of any crop sales.

Mrs. Emma Stallings Mayberry was 54 years-old and lived in a big old house on a lane near Park Station which is now called Rick Hight Road, just over the hill from Fred and Bob.

By the way, you know you’re getting old when you realize you personally knew everybody who has a road named for them. Rick Hight Road intersects with Fred White Road and Fred White intersects with Houston Cheek Road going north. Mr. Rick lived down the road from Fred and Bob. I knew them all when I was a boy.

In 1943, Miss Emma needed help. She was already walking with a cane from arthritis. Her son James Hardin had married and moved to town, and although her daughter Marie and her husband Fulton Fraser lived with her, Fulton was a car dealer and didn’t have time to work the farm.

Incidentally, years later, Fulton became a farmer and Walking Horse exhibitor who won the 1954 Championship Yearling Stallion and Grand Champion Yearling classes of the Celebration in Shelbyville. Fulton and Marie Mayberry Fraser also would sell the land on Bear Creek Pike for the current Tennessee Farm Bureau headquarters. Joe Frank Porter, who founded the Farm Bureau, married Miss Emma’s sister Pearle, and therefore was Marie’s uncle.

Jack had worked awhile for Miss Emma before she told him, “I’ve got an empty attic room and, if you’d like, you can live here at the house. I’ll cook your meals and you won’t have to walk over the hill every morning to come to work.” It was about a mile between the two houses.

Well, the White house was a real popular place in the community owing to my grandmother’s cooking. Hattie never knew who would show up at her doorstep on Sundays so she cooked like she was cooking for an army – three kinds of meats (old country ham, great fried chicken, beef roast), all kinds of vegetables (particularly cream corn, mashed potatoes and gravy, and butter beans), and big buttermilk biscuits and cornbread.

This also attracted guitar players and banjo players and fiddle players who would get together after Sunday dinner to make music. This was a pretty warm comfortable nest to leave but my dad liked the idea of walking out the back door to start work.

So, he began the new arrangement and one of the first things he had to do was to plow a garden. So he went into the barn and hitched up one of Miss Emma’s mules to a double shovel plow.

“She had two mules. I had broken both of them but this one was horsin’ and I hadn’t paid attention until we came out of the barn.

“I came out of that barn with that mule and he took off like a Black Racer snake,” said Jack.

“He came winding out of the barn lot into Miss Emma’s yard and that double shovel was bouncing up and down off the ground as the mule dragged it and me behind it.

“We went plowing through her flower garden and barely missed the cistern that stood beside the house. It was a narrow space between the tank and her back door and to this day I don’t know how we got through it but we went sailing around her backyard and chickens were scattering and squawking and flying wild as we flew past Miss Emma’s old Chevrolet car into the back lot.

“Finally, I got my footing and I started flailing away on that mule with the check line until I could dig in my feet and get his attention. Eventually he settled down and I plowed a garden.

“When I got through, it was time to milk cows, so I started on that before going back to the house to apologize to Miss Emma for plowing up her yard.”

While he was milking, he heard the tap of Miss Emma’s cane coming up the path to the dairy barn. Jack slowly and reluctantly turned around.

Much to his surprise, Miss Emma stood in the doorway smiling.

“Jack, I imagine you thought I came in here to bawl you out for plowing up my flowers…but instead I came to tell you that you remind me more of Hardin Mayberry than any man I know.

“He always said, ‘I go to the garden to plow the mule, not to let the mule plow me.’

“I want to tell you I appreciate you for plowing the mule.”

Then she turned and walked back to the house.

One day Jack was working in Emma’s hay field when Fred came riding up on his little Model G tractor. It had been half a dozen years since Doug had died and this was an odd scene for Jack to see, his uncle coming to look for him.

“Jake, I wonder if you can help me cut some hay,” he said.

“Sure, I can,” answered my dad.

Fred went on to explain. He had a fellow who lived on his place and he let him rent, thinking he might be help on the farm.

“…You know how to work the mower, and this old boy can’t quit yawning long enough for me to explain how to hitch up the horses. He don’t know nothing about harnessing a horse.” he said.

That was the beginning of the thaw between Fred and Jack.

Later on, Fred got sick after he had contracted out with a Mr. Stevens and two other farmers to set their tobacco. Although Jack was working at the Mayberry place, he made time to help out his uncle.

“Uncle Fred had two little boys who would sit up front on that Model G tractor, on either side of the plant box, and drop plants as Uncle Fred creeped along on that tractor…” The Model G was a three speed tractor with a reverse and a “creeper” forward gear for just such a purpose.

“…but I had three big patches to plant,” said Jack, “so I shoved it into 3rd gear and went to town. Those boys had a ball dropping those plants.”

The engine would do 1800 RPMs flat out, so Jack had probably jacked it up to 18 miles per hour from Uncle Fred’s 2.

” ‘Mr. Jackie, you can shore operate this machine,’ they would say. And, whenever I got to a hill, I’d throw it out of gear and we’d really fly.”

When Jack and the boys finally got to Mr. Stevens’ farm he was “pretty hot.” Fred was a couple of days behind on getting there and Jack told him he only had that day to plant.

“How in the world, you gonna get my field planted in one day!? There ain’t no way you can do it!”

“You can’t charge a guy for trying, can you?” replied Jack.

Mr. Stevens looked at the little boys and decided they needed incentive.

“If you boys get this field planted, I’ll have a reward for you.”

My dad went on to be one of the best truck drivers the Railway Express Company ever had, before working his way up to agent. He could drive everything from a delivery truck to a big semi. He was generously gifted in that regard and had a natural understanding of machinery. He had already figured out that if he locked up the left wheel on the Model G and slammed it into reverse at the end of a row, it would swing the front of the tractor around into the perfect position for plowing the next row.

At the end of the day, Jack and the boys came driving up to Mr. Stevens house and the boys each collected a shiny silver dollar.

“You never saw any bigger grins on two humans in your life,” said Jack.

Mr. Stevens told Jack, “I believe you could make that tractor suck a lemon.”

After awhile, Uncle Fred relied on Jack more and more.

“He got where he didn’t like to drive and wanted me to drive him everywhere. Once, we got in the old A-model and drove to Murfreesboro to pick up a bull calf from W. B.” My great-grandfather William Brantley White (my grandmother’s dad) raised prize Jersey cattle. His son W. B., Jr. “Bud,” took over the operation at 16 years old when his father died and turned it into a highly successful farming operation.

A side note: William Brantley White wore high celluloid collars and was a very distinguished looking guy. His sixteen-year old son Bud wore nothing but khaki Washington Dee Cee work clothes and was never seen without a big plug of tobacco in his mouth.

When W. B., Sr. died, the Murfreesboro farm was heavily mortgaged and the bank was about to foreclose. Sixteen year-old Bud walked in, propped his muddy boots on the banker’s desk and said, “Hoss, you can foreclose on my place and you’ll be left with a rocky hundred acres. But if you stick with me, I’ll get you paid.”

“How’re you going to do that?” asked the banker.

“I’m gonna give you me my whole monthly milk check ’til the farm’s paid off.”

“How’re you going to live?”

“That’s my look-out,” said Bud.

So the banker stuck with him.

Today, the original house stands on ten acres off Franklin Road, surrounded by a huge suburban housing development established by Bud’s widow and daughter.

Anyhow, Jack and Fred took the back seat out of the A-model and laid down a bunch of grass sacks to go pick up the bull calf from W. B. When they got to Murfreesboro, they caught the calf, tied a rope around his back legs to hobble him, and laid him in the back seat.

On the way back, about Eagleville, they encountered a road crew repairing the highway. Cars were stopped and backed up a good ways. Suddenly, the bull began to loudly and forlornly bleat.

People in the cars and the flag man were looking around wondering where the mournful strains were coming from. Jack and Fred looked around, too, like they were as curious as everybody else. They didn’t want to let on that in the backseat they had a bull trussed up like a kidnap victim.

It’s experiences like this that can bring an uncle and his nephew together.

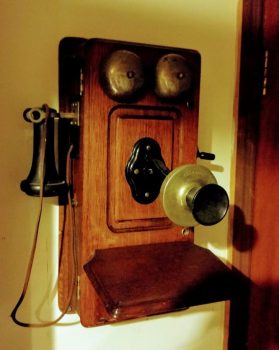

Many years later, after Bob died, Jack bought the old homeplace and we were neighbors with Uncle Fred — even communicating on our own direct-wired phone to Uncle Fred’s and Aunt Mary’s rather than using the 6-party land line.

For those too young to know, in the country the telephone lines used to be shared. You would check to see if anyone was talking, before you dialed a number. “Will you be talking long?” was a commonly heard question when someone picked up a receiver before dialing.

Fred and Jack became the best of friends again. When Fred and Mary moved to town, we followed soon after and lived just a street over from them in Riverside.

When Fred had a stroke and was in a nursing home for a few months before he died, my dad was one of his most frequent visitors. I remember seeing my dad sit by Uncle Fred’s bedside holding his hand.

So, thank the Good Lord, Fred had a lazy tenant. Otherwise, his nephew and he may never have made amends.

By the way, Jack’s farm arrangement with Miss Emma was short-lived.

“Miss Emma was a fine woman,” recollected Jack. “And I enjoyed working for her. But, bless her heart, she couldn’t cook for nothin’. And, when winter came, you couldn’t heat that attic room if you set fire to it…”

So, some time in winter, he decided to give up full-time farming and seek employment in town.