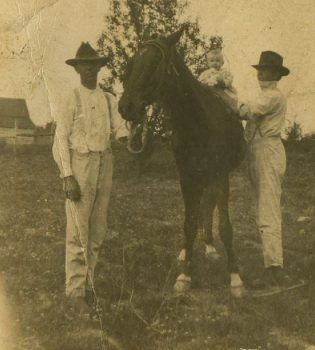

Hattie and Bob White (right) with their daughter and grandson — Dee and Tommy Brown.

note: The names in this story — except for my own family — have been changed to protect descendants of the others who I grew up with.

One night my dad Jack White and his father Bob were walking home from a tobacco sale. It was dark and cold and as they rambled over the tall, rocky hills toward their home in Scribner’s Mill, Bob was most aware of the wad of bills he carried in his coat pocket. Jack was about ten and would be little help in case of a hold-up.

Abruptly, a pitiful call sounded from the woods below. “Heeelp! Heeeelp!”

Bob and the boy stopped.

“Heeelp!”

The boy looked at his dad.

“We’ve got no business goin’ down that hill. We don’t know who it is. It could be somebody who cares to rob us.”

“Heeeelp!”

In the moonlight, the caller below could see the faces of the man and boy on the ridge.

“Bob! Bob White! Are you gonna leave me lie here to die and go to hell!!!???”

Suddenly, a look of recognition crossed Bob’s face.

“Why, that’s Paul Porch.”

Paul was a farmer, a neighbor, who had married the hardworking Polly Porch. Polly had inherited a big farm from her first husband, a school teacher and farmer, Bladon Wells, who was ten years her senior. He died of a perforated appendix at 31 years of age in 1917, leaving behind a young wife and two babies, a boy and a girl. Three years later, Polly married Paul, a man near her own age. By 1932, the household had grown to include three more boys and a girl — to number a family of eight, in all.

It took every kid and Polly, along with good neighbors and an occasional hired hand, to operate the farm.

Because Paul Porch was a drunk.

On his good days, he was a decent hand and would do “any-thing for any-body.” But those days were few and far apart.

When Bob and Jack wound down the wooded hill, they came to a fenceline where they discovered Paul’s horse, down on his side, with his hooves caught in the wire fence. Underneath the horse with his left leg pinned was Paul. He was holding down the rein with all his might to keep the horse from rising and tearing him apart.

Bob carefully kneeled beside the horse to survey the situation, then looked at Paul in disgust.

“You’re drunk.”

“Of course I am,” replied Paul.

“What were you trying to do? Jump the fence?”

“I didn’t see the fence.”

I ought to leave you here but I think too well of your animal.”

“Help me, Bob.”

“Well, if I help you, you better promise to ride home to Polly. I ain’t gonna risk a broke arm freeing you, if you leave for a tavern after I’m done.”

“I promise, Bob. You’ve got to help me.” There was fear and desperation in his voice and on his face.

Suddenly, Jerry Wallace, a hired hand and perpetual poacher sheepishly appeared from the woods.

“What’s happened here, Mr. Bob?”

It’s Paul Porch and he’s got his horse hung in the fence.”

It so happened, Bob had been working in the barn before going to the sale and had a pair of pliers in his coat pocket. He took them out and began to carefully clip the wire.

Jerry looked at the situation and produced an old broken file from his coat. He knelt on the other side of the fence and began to file the wire — with no visible success.

“A man can’t do nuthin’ when he got nuthin’ to do with,” Jerry mused.

“Get over there and get ready to pull Paul free,” Bob instructed Jerry.

Bob clipped the wire while Jack held the reins and Jerry held Paul.

When the hooves were free, Jerry dragged Paul sharply from the saddle as the horse shot from the ground with great force. Jack held the horse and kept him from running.

After awhile, Paul dusted himself off and stood unsteadily.

“Are you alright?” asked Bob.

“I imagine so.” Paul bent his knee and kicked a few times. Everything seemed to be in working order.

“Thank you, Bob,” said Paul.

“You remember what you told me, don’t you?”

“I sure do.”

Paul set a toe in a stirrup and slung himself into the saddle. He tipped his hat as he rode away — in the opposite direction of home and on a straight path toward the tavern.

Bob White (left) with his brother Fred and Fred’s daughter Ann Louise.

Some time after that, Polly asked my grandmother Hattie Mitchell White to come to the farm and help out with some task. As the women worked, Paul sat in the yard and drank whiskey from a jar.

After a few hours, the job was completed and Hattie walked into the yard. She was a sweet woman, accepting of every hard circumstance that came her way. She also was a kind woman who truly loved people, refrained from judging, and was always willing to help someone. BUT the sight of Paul drinking and sitting while Polly and she worked, was more than she could abide.

Not in a loud voice but in a tone firm as steel, she said, “Paul Porch, you ought to be ashamed of yourself. You need to quit this old foolishness. Take a bath. Put on some Sunday clothes and come to church tomorrow. Be an example to your kids.” Then she left for home, but not before turning to say, “I’m having fried chicken tomorrow. Y’all eat with us after church.”

The next day, the Porches were at Smyrna Church — and Paul was with them. My ten-year-old dad hardly recognized him. Paul’s hair was combed, he was clean-shaven, and he wore a very nice suit and tie. He actually was a handsome man.

After a big Sunday dinner — which included the eight Porches, six Whites, and whoever else sauntered over from Smyrna — Paul thanked Hattie for the good meal and said, “I can’t remember a better day than I have had today.” Polly and the kids seemed very happy, and proud.

Hattie Mitchell White

For the remainder of his short life (he died three years later at age 40), Paul made an effort to refrain from drinking and he would have periods of a few months when he was sober.

After he died, Polly moved the family closer to town and rented out the old Wells farm. One of the Porch boys, Leonard, didn’t want to leave the place. The renter was renting the land, not the house, so it would be empty. Leonard was determined to live in the house alone. He was twelve.

The family loaded all their belongings on a couple of old trucks and a wagon and moved on, leaving Leonard behind.

Since my dad was about Leonard’s age (Jack was a year older), Polly sent him to the house to reason with him. Nothing Jack said could persuade Leonard to leave the old house, so Jack decided to spend a few nights with him. The first night, they found a hapless Rooster, killed him, and set out to cook him in an iron pot in the fireplace of the empty living room.

“That was the toughest bird I ever tried to cook or eat,” remembers Jack 81 years later.

During the course of the night, Leonard looked at my dad and asked him a question.

“Jack,…was my daddy a drunkard?”

My dad looked at him for a moment. He felt great sorrow for the boy.

“Well, I’m not gonna say he was, but there’s no use telling you he didn’t drink.”

Jack White