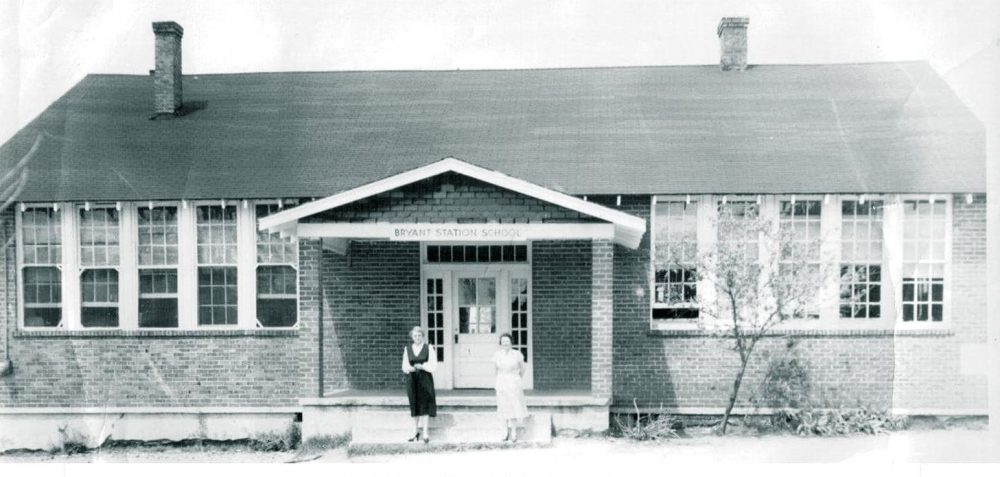

Bryant Station School held classes for first through eighth grades in a two-room schoolhouse. There were two teachers presiding, one also serving as principal. When Mrs. Willie Hight was principal in the 1950s, she drove the school bus, in addition.

In 1936, when my dad Jack White graduated from the 8th grade, the principal was twenty-five-year-old William Bryant “Bill” Orr. He was Dr. Billy Orr’s son and he lived in a big house on a hill that overlooked the school.

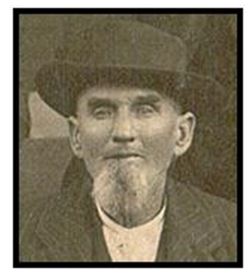

Dr. Orr was a prominent physician who lived on 85 acres given to him in 1891 by his father-in-law, the founder of Bryant Station, Andrew Daniel Dailey Bryant. Bryant is the man who built two miles of track, along with the switching and station houses named for him.

During the Civil War, Mr. Bryant served as Captain of Company H of the 53rd Tennessee Regiment and was a prisoner of war after the debacle at Fort Donelson. He was imprisoned at Johnson’s Island in Sandusky Bay in Lake Erie before being transferred to the notorious Camp Chase near Columbus, Ohio. Later he was part of a prisoner exchange at Vicksburg.

Bryant’s daughter Lizzie, the youngest of his eight children, married Dr. Orr in 1890, and the couple prospered. By 1902, Orr was partners in the Bryant grist mill and built the original general store across from the school.

The school was founded about 1899 and, in its early years, was overseen by a distant cousin from neighboring Marshall County, a spinster school mistress named Miss Annie M. Orr.

So, by 1936, the school was being run by a young man whose roots in the community were deep as a black gum tree – and Jack White loved Mr. Bill Orr.

This was due in large part because Mr. Orr invested so much confidence in the young boy, assigning him responsibilities such as bringing water from the Orr house to school, working math problems on the chalkboard that Mr. Orr readily admitted he couldn’t figure out himself, and even driving the school bus in the eighth grade!

Incidentally, bringing water to the school entailed roping a 10-gallon milk can to the front bumper of Mr. Orr’s old Austin, driving up the big hill, pumping water in the can, and returning to school. This was required because a well dug for the school had produced bad water.

The Austin, by the way, was difficult to start smoothly. When put into first gear, it tended to buck violently. Therefore, Jack always parked it on a hill where he could roll it and start it by popping the clutch.

One day his classmate Billy Pinkston accompanied him to the Orr place to change a tire on the Austin. When the task was finished, Billy begged so much to drive the car that Jack relented.

Only, when Jack pushed the car off the tall hill in front of the Orr house, Billy panicked and bailed out.

Thankfully, Jack was a fleet-of-foot thirteen-year-old or tragedy would have befallen the car and the boys’ backsides.

When my dad and four of his classmates — the entire, all-male, 8th grade graduating class – approached their final day in school in 1936, Bill Orr decided they needed to take a Class Trip in celebration.

He enlisted a 53-year-old bachelor, and relative of one of the students. Thomas Freeland, to chauffeur the boys and him to Nashville in Thomas’s old Chevrolet. Mr. Orr, a graduate of George Peabody College for Teachers, knew a lot about the town, and figured this would be an educational – and fun – excursion.

“One morning, we met at school and piled in Tom’s old car, all seven of us,” recounts my dad. “The plan was that we would sight-see all day and our parents would meet us at the store around 6 o’clock to take us to our homes.

“Well, Tom pointed the Chevrolet north, and there ain’t nobody could drive fast as Tom Freeland. I thought we were in a race. But that’s the way he drove all the time – although I think he sped up even more because he was excited about the trip as any of us.

“When we got to Nashville, Mr. Orr took us to all the sights he thought we ought to see – the Parthenon, the Capitol, the State Prison…

“Hours and hours had passed, we were walking downtown, it was late afternoon and we were at 7th and Union admiring the beautiful big stone building that housed the National Life and Accident Insurance Company, sponsors of the Grand Ole Opry.

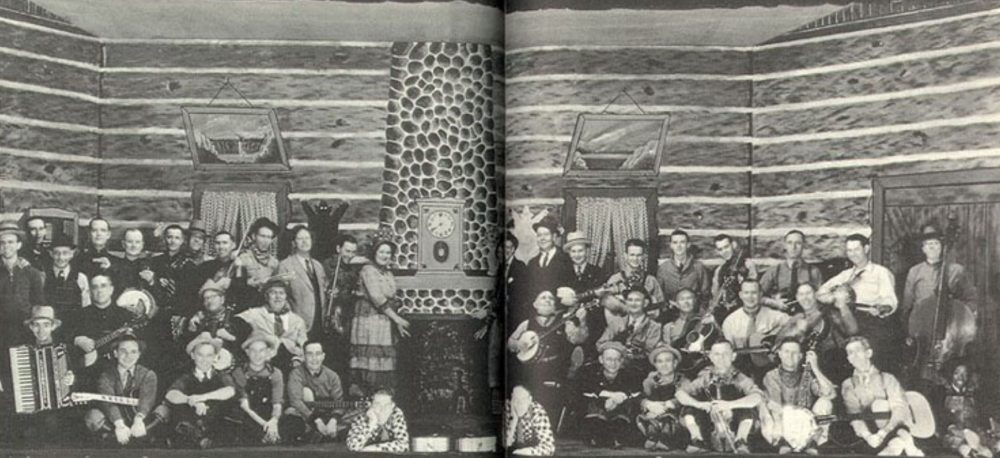

“Suddenly, Mr. Orr asked, ‘How would you boys like to see the Opry!?’

“Well, of course, we thought that was a grand idea! Mr. Orr ran in the building and, in no time, he came out with seven free passes in his hand. It was a free show then.

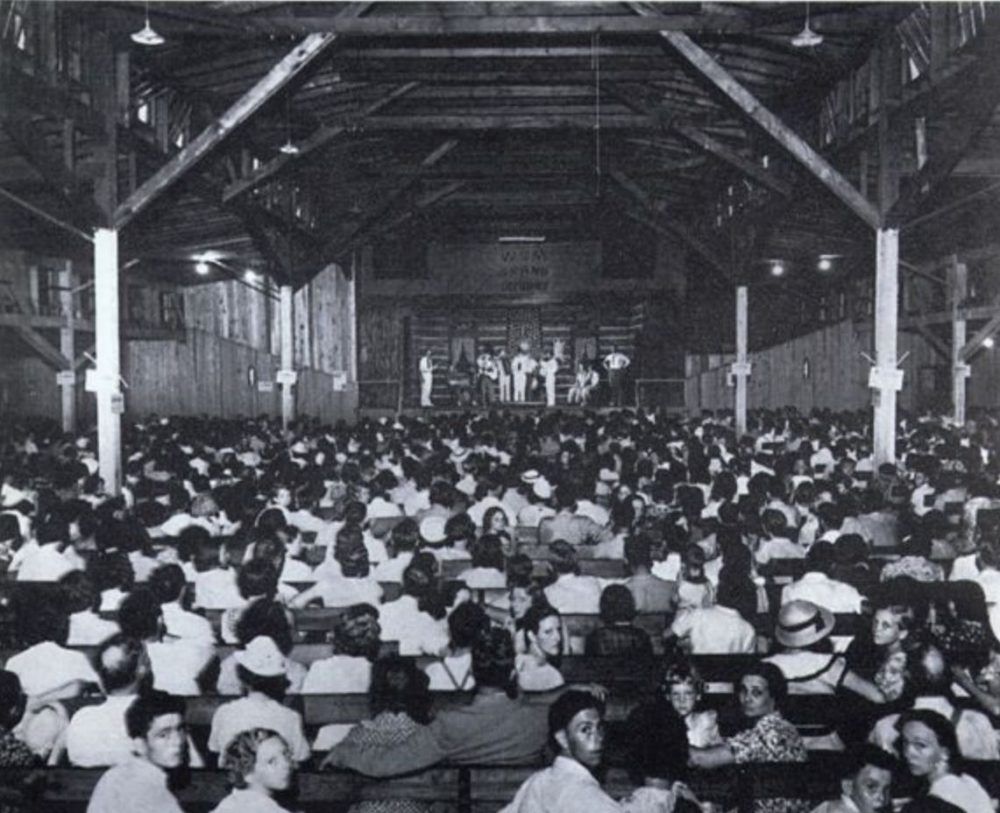

“So Tom motored us out to Fatherland Street in East Nashville, to the Dixie Tabernacle! This was the brand new home of the Opry.”

The Opry had moved from WSM studios to the Hillsboro Theater (now the location of Belcourt Cinema), before moving to the Tabernacle.

“It was a big revival tent, with rolled-up canvas sides, dirt floors, and wood benches on concrete blocks.

“A man was outside cooking hamburgers and I unloaded some of my trapping money to buy a couple. We had been walking all day, and were so excited, we had failed to eat.

“Well, it was a great show – Uncle Dave Macon and a whole crew of folks I can’t remember. I think maybe Sam and Kirk McGee, Curly Fox and Texas Ruby…it’s been a long time ago. But the show went on and on and we loved every bit of it! We were watching in the flesh, in living color, what we’d been listening to in the dark as a crackling noise on an old dry cell radio, way out in the country.”

If Bill Orr wasn’t Jack’s hero before, he sure was now.

“It took a long time to get home on the old Nashville Highway and we didn’t pull in front of Dotson Hardison’s store until near midnight.

“And there were all our parents waiting on us. They were half crazy with worry. None of us had thought to call the store to tell them we’d be late! Mommas were crying and daddies were sputterin’ and spittin’. My dad, in particular, was fit to be tied.

“But Mr. Orr just stepped out of that Chevrolet smiling. He calmly waved to everybody, got in his in Austin, and puttered up the hill.

“He never offered the first apology.”

The boys had a good time and that was all that was important.

A little over twenty years later, the old tabernacle burned down. By that time, it was a rundown, abandoned eyesore that hoboes built fires in to spend the night.

Today, most of my dad’s memories are smoky as that old tent, but because of Mr. Bill Orr, he has one story that’s survived the fire.