My father was a Railway Express Agent in Columbia, Tennessee. Here are a few topics that came up in conversation after Thanksgiving dinner.

Mr. Hardaway was the agent (manager) of the Railway Express Agency (REA) in Columbia, Tennessee in the early 1960s. He was nearing retirement when he became ill. The district manager in Atlanta called my dad, Jack White, in Cookeville and told him to return to Columbia to take Mr. Hardaway’s place. My dad was a delivery driver in Columbia but was being groomed for management. He was doing “relief” work where he took the place of agents at a series of depot offices while they took their vacations. He had completed three to four week stints at Athens, Alabama and at Tennessee depots in Springfield and Cookeville. He was next scheduled to go to Bremen, Georgia.

Unbeknownst to my dad, Columbia business people had gotten together to sign a petition that he be the next agent of the Columbia office – everyone from the plant managers at Monsanto and Union Carbide to downtown merchants. They sent the petition to New York and copied the Atlanta district office.

My dad was a big friendly, hard-working guy who also was known for his honesty and strong character. He also was a part-time Church of Christ preacher. People liked and respected him.

Later, when my dad heard about the petition, he always suspected that his cousin’s husband Ralph Andrews who worked in the bookkeeping department at Monsanto had started it. Ralph never confessed to it.

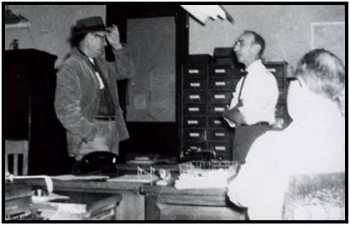

On his first official day on the job, a man was waiting on my dad at the office. The man asked, “Are you Mr. White?” and my dad replied, “Yes I am, Mr. Hall.” Hall was the district manager from Atlanta.

“Have we ever met?” asked Hall.

“No, but we’ve talked on the phone several times.”

“Well, that’s just real remarkable that you would know me by just the sound of my voice,” said Hall

When my dad told me that story, he said, “He had a voice that was all to himself.”

My dad had handled thousands of dollars each day that came in by train – “remittances” sent from the five county offices for which he was responsible. A remittance was the money collected that day from deliveries, signed and accounted for, then put into a big sealed manila, string and button envelope. The envelope was sealed by burning a wax candle, then stamping it with a heavy stamp marked with the town name and depot number.

The amount of the day’s express deliveries was written on the outside of the envelope. When the money arrived in Atlanta, and the seal was broken, that meant somebody had robbed the company. It was pretty easy to track where the robbery would have taken place because it was signed by the agent, the Train Messenger, then signed by person receiving the funds in Atlanta.

If the amount of money inside didn’t match the number on the outside of the envelope, that meant the agent was responsible for the difference.

My dad would make up the Columbia remittance, collect the other envelopes, then put all the envelopes into a canvas bag before taking it to the Train Messenger. He would count his collections at his desk which sat in the middle of his small block warehouse office on the east end of the old depot. The room was about a 40’ by 40’ with at least 12’ ceilings for stacking the boxes high. It not only held boxed shipments but it also contained wire crates of everything from carrier pigeons to bird dogs to alligators to rattlesnakes.

Big sliding doors were on either end of the office and they were open most of the time. By the way, he built his own “office” halfway down the east side of the room. It consisted of a counter and an open wood cubicle that blocked off his desk, safe, and a work table from the cargo.

He said, “The only time I got scared working at the depot was one night when I was counting a big stack of money. It was winter time and it had turned dark early. I looked up and saw, standing in the doorway, three men. They were about 20 feet away in the shadows. I couldn’t see their faces but I could tell they were staring at me.”

He said, “I had just worked the train and I still wore my .38 revolver [which wearing a gun was a regulation for agents unloading trains in those days]. So I slowly drew the pistol from my scabbard and laid it on the desk, in full view, in front of the stack of bills which I kept counting. When I looked up again the men were gone.”

Speaking of remittances, there was a Train Messenger named Dobbs (name changed to protect his unfortunate family). His job, among others, was to oversee and guard valuable private shipments, especially those that were secured in a safe or strongbox. Each day, he signed for the remittances and put them in a safe in his express car which carried them to Atlanta.

One morning, my dad was loading a large wooden crate onto the express car and the top came loose. Both Dobbs and my dad could see that the crate was full of bottles of Kentucky bourbon.

That night, when the train rolled back in, Dobbs’s express car doors on both sides were wide open. My dad looked in and Dobbs was lying in a corner drunk and passed out. The safe was open and remittance envelopes were scattered all over the floor from flying around in an open box car. My dad didn’t disturb Dobbs. He just gathered up all the envelopes, put them with his remittance, signed all the papers, then put the money in the safe and locked it. He then closed the express car doors and the train pulled away.

The next morning, my dad was waiting for Dobbs. He said, “Yesterday I did you a tremendous favor.”

Dobbs, a little indignant, said, “What?”

My dad explained to him what had transpired, then he ended with, “…and that’s the last time that will happen. The next time you show up here in that condition, I’ll write you up to the railroad and the express company.” Dobbs said, “You wouldn’t do that…” and my dad said, “You don’t want to try me.”

Some time later, the train pulled in one day and Dobbs informed my dad, “I ain’t taking no shipments today.” Another of the Messenger’s jobs was to sort the shipments once they were loaded into the express cars. Dobbs had a hangover or otherwise was in a foul mood and he didn’t want to work any more that day. My dad said, “You’ve got two doors on that box car. Open the other one and you can kick these boxes out as we load them if you want to but we’re loading.”

My dad said, “He was just wanted to see if he could run a bluff.”

Another time, a bluff — and a firearm — came into play.

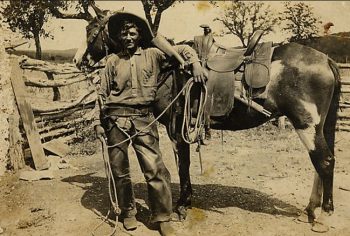

There was an old Oklahoma cowboy named Hargrove, of no relation to the Maury County clan, who lived at the depot. His wife and he had an apartment on the north side of the building, on the second floor, opposite the trackmaster, an old bachelor who literally lived above the tracks.

Hargrove was the night watchman. He slept during the day. At night he would strap on his old gun belt, grab a big flashlight, and make his rounds.

The old scabbard was heavily scarred from days in the saddle. This fellow was of retirement age in the 1950s so he was old enough to have ridden the range during some pretty rough and woolly days out west.

Among his duties in winter was to fire the old furnace in the basement which presumed to heat the whole three story building.

“Those people in the upstairs apartments had little electric heaters or they would have frozen to death,” said my dad.

One night my dad was working the train on the midnight shift and Hargrove walked into his office.

“He was white as a sheet. He asked me, ‘Can you come down in the basement with me?’ and I said, ‘Sure. What’s the problem?'”

“I went down to fire the furnace and I heard somebody strangle a cough in the dark.”

“Well, let’s go see…”

So the men went down to the basement and Hargrove switched on his flashlight. He threw the light around the dirt, hand-dug room until it fell upon a man lying in a makeshift bed of cardboard boxes perched upon a dug-out shelf.

“It was perfect size for a single bed,” recalled my dad.

The man stared back with wide eyes.

Hargrove slowly drew his old six-gun revolver.

“Fellow,” he said, “if you were to come to me and ask me for a place to come in from the cold, I’m liable to have helped you. But as it stands, you’re trespassing on railroad property…so I want you to get up, and I don’t want you to walk out of here. I want you to run. And if you stop or look back, I’m gonna kill you.”

My dad said that man jumped up and took off as hard as he could go.

“He forgot he was asleep. And he never tested whether Hargrove was serious. He ran out of sight without ever letting up.

“I felt sorry for him and I think Hargrove did, too. But he had bedded down unannounced.”

I stole this story for my book, No Kin to Elvis, although I changed the setting to 1917 at Camp Holland at Viejo Pass in Texas.

I asked my dad if he ever saw anyone badly hurt on the tracks all the time he worked at the depot. He said, “One night, I was training a new man on the job and we were pulling our freight wagons down the sidewalk runway between the tracks. He was in front of me. I looked down and I thought I saw him lying on the track.

“But it was a stranger lying partially on the runway and part on the track. He had been walking on the runway and probably had walked between our parked wagons and the passenger cars without paying attention to the steel grab bars on the side of the cars. One had knocked him out and he had fallen on the tracks and the train had run over his hand.

“I kneeled down by him and saw that the top half of his hand had been ground like sausage by the wheels. I put him on my hip, and carried him inside the ticket office and I told the ticket agent, ‘Call the hospital. This man needs a doctor right away.’

“When the agent saw what had happened, he said, ‘We better get him a good doctor. Put that man on the passenger train. I’ll wire ahead to the ticket man in Nashville and he’ll have a doctor waiting at the depot.’

“So we wrapped his hand and set him on a passenger seat and he went to Nashville.”

There was no heat nor air conditioning in the depot warehouse, save for a small electric heater near the counter. In the winter time, the big sliding doors were open almost constantly. By the way, Middle Tennessee winters of the 1950s and 1960s could be pretty harsh. In January 1966, the temperature got down to -13 degrees, and 6 to 7 inch snowfalls were not unusual during that period.

To petition for an industrial heater, my dad had to go through a district “Commercial Agent” who summarily refused the request. The Commercial Agent also was responsible for soliciting business in the district – a job for which he was ill-suited. My dad solicited and took care of his own business.

One cold winter day, the Commercial Agent came by for a required visit. He sat by my dad’s desk as my dad did paperwork. Once in awhile, my dad noticed the agent would flinch from the cold.

“You haven’t got any heat in this place?” he asked.

“Sure. I’ve got this electric heater. Are you cold?”

“Man, you need some heat in here! I’m going to the hotel.”

“What’s wrong? You didn’t seem to think we needed a heater when I asked for one.”

The man left and in a week or so, an industrial gas heater was suspended from the ceiling. My dad said, “It was still cold in there because we had to keep sliding those big doors open. But it helped.”

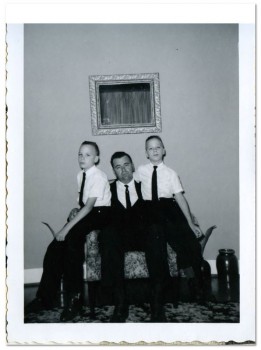

The depot was in a neighborhood that prosperity had forgotten. There were mostly poor kids who walked the tracks home. Once, when I was a kid, I had begged and begged and begged my dad for a fancy Roy Rogers toy stagecoach that I had seen advertised on television. It was made by the Ideal company and it featured Roy and his sidekick Pat Brady sitting on the driver’s box. It had a strong box and doors that opened, and Bullet the Dog, and it was pulled by four golden Palomino horses that were no doubt related to Trigger. It was really outstanding.

Anyway, I asked my hard-working dad why I couldn’t have it, and he explained to me that he couldn’t buy me “everything I wanted.”

So a couple of weeks passed by and I was at the depot and, somehow, during a conversation unrelated to the Roy Rogers stagecoach, I exhibited to my dad a very unappreciative attitude about some other subject.

My dad looked at me, then slowly rose from his desk. He walked to the counter, reached under it, and pulled out a package. He unwrapped the package. It was the Roy Rogers stagecoach!

I was ecstatic!

Without saying a word, he walked out of the depot onto the tracks. About that time, a poor downtrodden boy about my age at the time — six or seven years old — was walking down the tracks.

My dad approached the boy and held out the Roy Rogers stagecoach to him.

“You reckon you’d like to have this?”

The little boy’s eyes got big as saucers.

“Yeah…SURE! Yeah, I would! THANK YOU! THANK YOU!”

Meanwhile, I’m sort of in shock. My daddy is giving away a perfectly good Roy Rogers stagecoach that by all rights and heavy begging should belong to me.

“Well, I hope you enjoy it,” said my dad, and he gave the boy the big shiny box with the big “Ideal” logo on it that contained the stagecoach.

Then he walked back inside the depot.

I watched the happy boy walk down the tracks with my Roy Rogers stagecoach.

After a while, I walked into the depot. My dad was burning a wax candle, sealing his big remittance envelope.

With his eyes on the burning wax, he said, “Now there’s a young boy who appreciates things.”

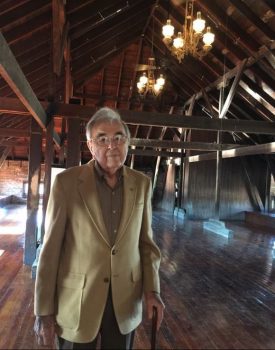

Recently, my dad returned to the newly-restored depot by gracious invitation of the owners, David and Debra Hill.