On November 7th of 1940, as World War II seemed imminent, Paul Reuben Wing, a 49 year-old Hollywood filmmaker, decided to reenlist in the Army.

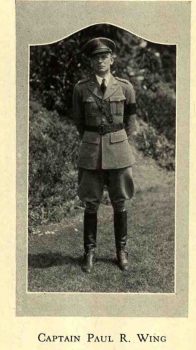

In the previous war, he had advanced to the rank of Captain with the 19th Field Artillery Regiment of the Red Diamond 5th Division while seeing action in “five major battles and two minor engagements” during the victorious St. Miheil Campaign of September 12-16, 1918.

Additionally, he served as an aerial reconnaissance photographer, most likely as a forward observer for the artillery.

He eventually parlayed his photography skills into a new career with Paramount Studios after resigning from the military in the mid-1920s. In a variety of capacities, he served film crews with distinction on such important productions as Stark Love (1927) and The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) starring Gary Cooper. For the latter, he won an Oscar for his work as Assistant Director.

Along with his outgoing wife, his son, and his beautiful daughters, Paul became a well-liked member of the Hollywood community. He built a house on Rodeo Drive and the Wings entertained a duke’s mixture of friends the like of Amelia Earhart, W.C. Fields, J. Edgar Hoover, Gary Cooper, and Shirley Temple.

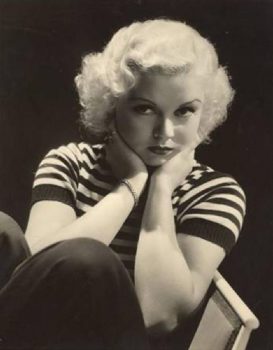

In the 1930s, Paul’s daughter Toby became a sensation in Hollywood. She was known as “the girl with a face like the morning sun.” An original member of Samuel Goldwyn’s musical stock company, the Goldwyn Girls,” her suitors included Hollywood royalty and the cream of New York society –Maurice Chevalier, Franklin Roosevelt, Jr. , and Albert Vanderbilt.

Throughout the family’s success, Paul Wing continued to be well grounded. During his peak Hollywood years he even served as a volunteer R.O.T.C. instructor at Los Angeles’s Lincoln High School.

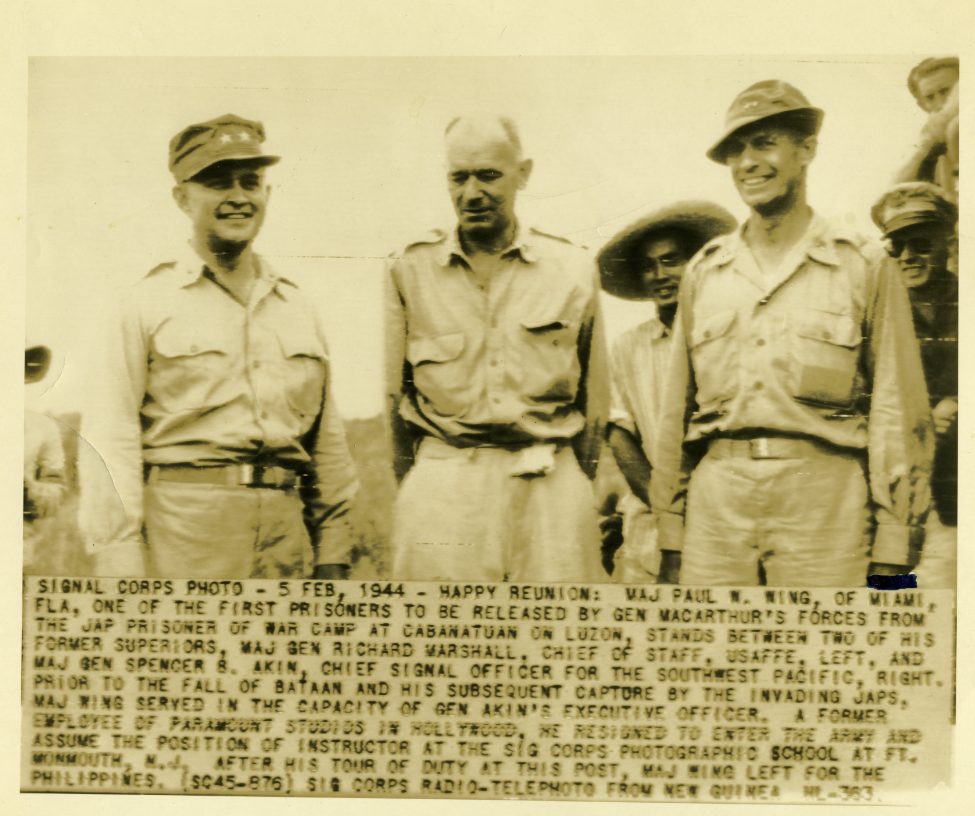

Perhaps this played a part in his decision to re-enlist when he saw war on the horizon. After training young men to serve their country perhaps he felt an added responsibility to join them when the Army requested his services with aerial reconnaissance in the Philippines. He joined the Signal Corps in 1940 with the rank of Major, and after a short assignment as instructor at the Fort Monmouth, New Jersey Photographic School, was assigned to General Douglas MacArthur’s staff as executive officer to General Spencer B. Aiken.

When the Japanese 14th Army began their invasion of the Philippines on December 8, 1941, Paul Wing was away from headquarters on Bataan assisting in building a road at an air strip. Consequently, he joined the desperate defense of the peninsula with his fellow soldiers from January 7 through April 9, 1942 when Major General Edward P. King surrendered his troops to Major General Kameichiro Nagano.

The surrender followed months of bloody fighting against staggering odds with scant food and munitions as General MacArthur’s famous Plan Orange-3 fell apart with no hope of support from the crippled Pacific Fleet. MacArthur sailed away in a PT Boat for Mindanao, leaving the defenders behind, later issuing an order to General Jonathan M. Wainwright at Corregidor:

“I am utterly opposed under any circumstances or conditions to the ultimate capitulation of this command. If food fails you will prepare and execute an attack upon the enemy.”

The final blow to Bataan was a constant 6 hour bombardment by 100 Japanese planes and 300 artillery pieces of the Mount Samat fortification from early morning to the mid afternoon of April 3.

Corregidor fell a month later thereby bringing the defense of the Philippines to an end.

So, at 50 years old, after enduring one of the most horrific battles of the war, Paul Wing joined 60,000 Filipinos and nearly 15,000 American soldiers, most starving and disease-ridden, on the 90 mile march from Mariveles to captivity at Fort O’Donnell in the Tarlac province, a camp which had been prepared to receive 25,000 prisoners of war. This came to be called The Bataan Death March.

Out of those who began the march, thousands died before reaching the prison camps. The exact number of casualties is impossible to determine but conservative estimates are between 6,000 to 11,000 men.

Again, photography played a role in Paul Wing’s life. He concealed a camera during the march which he used to secretly photograph the conditions of the men and the atrocities they suffered at the hands of their captors.

Eventually, Paul was sent to Cabanatuan where fellow P.O.W. Sergeant Abie Abraham recalled that he was highly respected and liked by the men. “I washed his clothes and brought him food…He stayed in relatively good physical condition during our captivity…He was a gentleman.”

Incredibly, his son Paul Jr. on hearing that his father had been captured, lied about his age and enlisted in the Marines at 15 years old. His mission was to get to the Philippines and rescue his father.

On learning what had happened, Martha called her good friend J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who found Paul Jr. and brought him back home. Yet, when Paul Jr. reached age 16 in December of the same year, he somehow convinced his mother to sign a consent form and he again joined the Marines; however, his assignments did not take him to the Philippines.

Paul Wing. Sr. was a P.O.W. for nearly three years until rescued January 30, 1945 by U.S. Army Rangers, Alamo Scouts and Filipino guerrillas. This was the famous Raid on Cabanatuan written about by Hampton Sides in Ghost Soldiers and later made into the movie, The Great Raid.

As astonishing as it seems, Paul took photographs during the raid as the gunfight blazed between his liberators and the Japanese guards.

When Paul and the rest of the men were transported to safety, their doctors and nurses sensed a feeling of sadness and apprehension among the men. Eventually, it became apparent that the former prisoners of war felt they would return to the United States in disgrace. They believed the American public would consider them cowards for not fighting to the death at Bataan. Even General Wainwright, on meeting MacArthur in Tokyo Bay at the signing of the peace treaty in September of 1945, wept and begged forgiveness of his former superior for surrendering Corregidor. Wainwright was certain that a court-martial awaited him.

James Webb recollected his feelings on witnessing this scene:

“Wainwright had carried the load, had fought the impossible fight, suffered the insufferable, borne the unbearable. And here he was begging for forgiveness from the very man who had left him and the others behind to suffer death, starvation, and captivity.”

According to his family, Paul Wing never completely overcame his feeling of shame for surrendering. Sadly, this emotion is apparent in the news wire photo of his liberation. He avoids looking at the camera as his former superiors smile broadly, thankful for his rescue.

Far from returning in dishonor, Paul was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, and, for his actions at Bataan and for secretly documenting the atrocities at Cabanatuan, he was awarded the President’s Citation, Legion of Merit, the Purple Heart, the Oak Leaf Cluster, the Philippine Government Decoration, and 6 battle clasps.

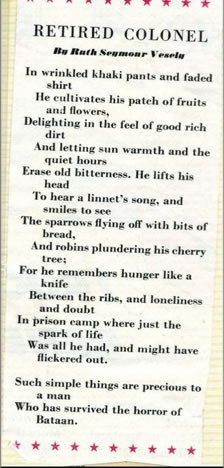

Understandably, when he returned home to his family he was a changed man. The tremendous ordeal had taken its toll on his heart. Though in failing health, he bought a beautiful farm in Mathews, Virginia called Shadecliff. There he farmed, made furniture and enjoyed nature and the out of doors with his wife and family. He became a much beloved member of the Mathews community, attending the Episcopal Church, serving as a Royal Arch Mason at the local lodge and a Commander of the American Legion Post.

A poet, published in national magazines of the 1950s, Ruth Seymour Vesely wrote this about Paul and his life in Mathews:

Paul Wing died peacefully at Shadecliff in 1957 at the age of 65.