This is an unpublished article about Paul Wing who was featured in the movie “Stark Love”

PAUL WING: HOLLYWOOD’S TRUE LIFE HERO

In 1889 three brothers from Maine journeyed to Tacoma, Washington. Two were doctors and one was a storekeeper. The doctors had come to join the staff at the Fannie Paddock Hospital which had just relocated from its original home on Starr Street to “a new and commodious building…in the most healthful part of the city.” The new 4-story, 100-patient facility was built on J Street between South 3rd and 4th.

The hospital’s expansion was in response to the city’s burgeoning population during the boom time after the coming of the Northwest Pacific Railroad and its transcontinental track. During the 1880s, the little hamlet of Tacoma, with a population under eleven-hundred residents, grew to a city of more than thirty six-thousand, and the three brothers – Peleg, Ellery, and Lory Wing – were part of the wave.

The Wings were a family who could trace their American roots back to the Plymouth Colony of the early 1600s. Four generations came to settle in Livermore, Maine from whence the brothers traveled, and where their father Lewis plied a variety of trades. A big man (6’2” and 235 pounds), he had been a school teacher, a deputy sheriff, a town selectman, and a county coroner, before inheriting a 100 year-old family farm.

The sons were “reared in a home of New England simplicity and high ideals.” Their western migration followed the death of their mother and preceded Lewis’s impending sale of their childhood, ancestral home. Peleg’s failing health and perhaps the upheaval their family life spurred the brothers west yet, by this time, Peleg and Ellery were well-traveled and highly-educated young men. Both had graduated from Hebron Academy boarding school and Bowdoin Medical College. Peleg had also earned a degree from the New York Post-Graduate School of Medicine (now part of New York University School of Medicine). He was a specialist in diseases of the ear, eye, nose, and throat and later became a renowned Fellow of the College of Surgeons, having studied at the University of Vienna. He eventually traveled throughout Europe – Edinburg, London, Paris, and Berlin — visiting hospitals and consulting with the world’s leading surgeons.

When the brothers first arrived in Tacoma, Peleg and Ellery set up shop at 14th and Pacific Avenue, then were the first occupants of the old Tacoma Theater Building (later known as the Music Box) which covered a city block on Broadway. Ellery left after 5 years and returned to Maine where he became a leading physician, holding a prestigious office in the State Medical Society.

Peleg – and Lory as a mercantile man – prospered, as well. In 1911, Lori built a substantial craftsman bungalow-style house on North Grant Avenue that still stands and is on the National Historic Register.

Peleg especially loved the wilds of Washington and became a capable and enthusiastic big game hunter. Yet, he must have harbored a longing for his old home and family. Evidence of this was his growing interest in genealogy. He began subscribing to a well-produced quarterly publication called “The Owl” which was printed by the Wing Family Association. In 1907, he traveled to Boston to attend a large family reunion and was elected a board member.

This must have instilled in him a great deal of pride for his family and a sense of responsibility for upholding the Wing name. A typical front-page column of “The Owl” in 1917 extolled the Wings for their long tradition of American patriotism:

The Wing Family of America will do its full duty in the present war. They began their patriotic service in America as early as 1675, when Ananias and Stephen Wing served in the Plymouth County companies in the Narragansett War. Something like sixty of us carried guns in the War of the Revolution, and The Owl has published the official records of over 500 of our name and blood who were soldiers in the Civil War. The traditions of the family are being upheld in the present war with Germany…

The Owl goes on to name 15 Wings from nearly as many states who were enlisted in the American Expeditionary Forces headed for battle in France. One of them was Peleg’s only child, Paul Reuben Wing, at the time a 1st Lieutenant of field artillery.

Paul was the first of his line to be born in Tacoma, arriving August 14, 1892. He was a tall, handsome, ramrod-straight young man with a solid character, the pride of his parents and a credit to the Wing Family of America. Paul spent his childhood years in Tacoma before leaving for prep school at Staunton Military Academy in Virginia – and this is where, in the eyes of his father, he disgraced the Wing name. He fell in love with a Southern Belle.

Peleg, as can be imagined, having a New England pedigree dating back to the Mayflower, was devoutly pro-union. The young woman in question, Martha Gillis Thraves, was the daughter of John Thraves, master of Amelia County’s Right Oaks Plantation and a veteran of Company H of the 44th Virginia Infantry, C.S.A.

Both families protested the forthcoming marriage. The Thraves were as much opposed to it as the Wings. However, Paul and Martha ignored the objections of their kin and were married Christmas Day, 1912. Immediately they were both disinherited.

Shockingly, 4 months later Peleg Wing divorced his wife. Thirteen months later, he married his ex-wife’s niece who was 19 years younger. Despite the scandal (for 1913), Peleg continued to live and practice medicine in Tacoma.

Surprisingly, Paul returned to Tacoma to find work. Back in his hometown, he joined the Washington National Guard and, while working other jobs, began developing a new interest, photography.

Photography had its applications to Paul’s military career. With the American Expeditionary Force in France in the Fall of 1918, Paul advanced to the rank of Captain with the 19th Field Artillery Regiment of the Red Diamond 5th Division. Additionally, he served as an aerial reconnaissance photographer – most likely as a forward observer for the artillery. Along the way, he saw action in “five major battles and two minor engagements” during the first American operation and victory of the war, the St. Miheil Campaign, September 12-16, 1918.

During this period, some of Paul Wing’s photographs – aerial and otherwise — were used, not only for military purposes, but for publication in popular American magazines.

Soon after the Armistice on November 11, 1918, Paul Wing was transferred to the Panama Canal Zone. By then, Martha and he were joined by two daughters, Gertrude and Martha Virginia, who was called Toby.

By the war’s end, Peleg was 58 years old and in failing health. He had become eye surgeon for the Northwest Pacific and the Chicago & Milwaukee railroad lines. Washington’s Industrial Insurance Commission and the U.S. Pension Board often called him as an expert witness regarding claims. His many professional and civic responsibilities eventually weighed too heavily upon him.

He decided to retire from practice in order to regain his health. He moved to a lemon and orange grove in Escondido, California with his wife and their daughter Pauline Lucretia, born in September of 1914.

In the mid-1920s Paul suffered a temporarily debilitating accident, said to have been a plane crash while shooting aerial photographs. Regardless, by 1926, he resigned the military and left his beloved Panama due to a “disability.”

At least two years before his discharge, Paul was trying to determine his next move. Martha and he read about homesteading opportunities in Lake Elsinore, California. In the 1920s, the government gave a person title to public domain lands, in some cases 150 acres or so of surveyed property if, in exchange, they would reside there for a specified period of time (typically, 5 years) and make specified improvements or meet other conditions, such as raising cattle or installing irrigation. On Paul’s land he attempted to farm and, amazingly, to work an abandoned gold mine.

Martha also was in search of gold. It is not clear how she broke into the movies. Her grandchildren remember that Paul had a studio connection through an army friend. He may have reconnected with this person at Lake Elsinore which, in the 1920s, was a popular get-away destination for the movie crowd.

At any rate, by 1924, Martha – a lifelong, expert equestrian — had parlayed her skills into a stunt riding job for some of Hollywood’s biggest female stars, namely Mary Pickford and Marion Davies.

For extra measure, she decided that her beautiful daughters, then 9 and 10 years old, could also contribute the family coffers. Toby Wing appeared in 6 motion pictures between 1924 and 1926. She would become an extremely popular platinum blonde starlet of the 1930s, making 39 more films before her retirement in 1938 at the age of 23. Her older, beautiful — yet less ambitious sister — Gertrude (billed as Pat or Patricia Wing) played supporting or extra roles in 20 films between 1932 and 1934. In 1926 a baby brother, Paul Jr., joined the family but never evidenced a desire for stardom.

One can speculate as to who might have been Paul Wing’s Hollywood connection. Interestingly, when Paul was an aerial photographer with the 5th Division, legendary photographer Edward Steichen was in charge of the AEF’s Photographic Division of Aerial Photography. This may have been Paul’s indirect contact to the studios.

Already renowned by 1918, Steichen’s fame grew through his Vanity Fair and Vogue photographs which are often described as “setting the standard for 20th century magazine photography.” Steichen may have been responsible for placing Paul’s photographs in magazines, which may have caught the attention of another influential AEF officer, Lieutenant Walter Wanger of the Signal Corps.

A theatrical producer before the war, Wanger worked for the Committee on Public Information, a war propaganda unit. In that capacity, he placed a great deal of the printed and filmed material produced by the army for popular American consumption.

Regardless who helped Paul into the motion picture business, when he retired from the military in 1926 he went to work for Paramount Studios, a film company for whom Walter Wanger was the general manager. Little did he know he was about to experience a challenge nearly as life-threatening as St. Miheil.

From the beginning, Paul impressed his employers at Paramount. An early assignment, perhaps his very first, was to serve as business manager on a highly unusual film which since has been recognized as one of the best movies of the late silent era, Stark Love (1927).

This experience, documented in the director Karl Brown’s memoirs, provides a snapshot of Paul Wing, the filmmaker, in action.

Karl Brown, an accomplished cameraman for the likes of D. W. Griffith, was shooting his first film as a director. He had a highly unusual idea for a movie. He wanted to shoot a film about real mountaineers living in Appalachia, somewhat on the style of Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North.

One of the first men Brown hired for his crew was Paul Wing. Initially he hired him to be the business manager but it soon became apparent that this resourceful ex-artillery officer could contribute far more to the project. Eventually, Paul became the assistant director. Informal photo stills of the set show him at Karl Brown’s side watching the action. Additionally, Brown asked Paul to help cast the film and to supervise all the heavy construction tasks the remote location shot required.

Along with cameraman Jim Murray, a former cavalryman, Brown had two seasoned military men who would prove to be ultra-competent, unflappable dynamos.

Karl Brown, a private in World War I who had spent most of his service time in sick bay with the Spanish influenza, immediately recognized his good fortune:

…An even odder thing, from my civilian point of view, was the correctness with which they followed ingrained military protocol. The instant I entered a room they were on their feet, at stiff attention. After a little thought I arrived at what proved to be the correct appraisal. They were not respecting me but my position, which was that of their commanding officer. Their private opinions of me were their own, but their official behavior was a matter of fixed military protocol. I had only to hint at something I’d like to have done, and boom! It was the same as done and on the double, too. You might think this would have gone to my head and made me insufferably vain. The contrary. I had one hell of a time living up to my help.”

Fortunately, Brown also recruited the services of legendary Appalachian writer Horace Kephart who recommended the rugged Unicoi Mountains near Robbinsville, North Carolina as the perfect movie setting.

The Tallassee Power Company was building a dam on the Cheoah River. They had displaced an entire community near, what is now called, the Nantahalah National Forest. The dam would not be completed before 1928 so its construction would not interfere with filming. The abandoned cabins and deserted landscape presented an ideal wilderness movie set.

In the manner of Robert Flaherty, Brown was determined to cast his film with local non-actors. Paul Wing played an important part in this task as he searched nearby towns when casting four of the major roles which, in Robbinsville, had proved to be impossible.

Through Paul’s help, Brown realized his objective to cast amateurs for his movie. However, his dream to exclusively use authentic mountain people for Stark Love proved to be very difficult. Ultimately, there were three “city” actors employed for the shoot: Helen Mundy, a 16 year old Knoxville flapper who had appeared as a dancer in a George White’s Scandals road show; Forrest James, a three-sport letterman at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University); and, playing the key role of the Circuit Preacher, a 34 year-old ex-artillery officer, Paul Wing!

Incidentally, the Circuit Preacher is a virile outdoorsman who rides a horse through swift-flowing creeks and steep mountain trails. Throughout the ride, Paul’s posture is cavalry-perfect and his posting is expert.

Brown filmed through the summer of 1926. Thanks to the engineering and organizational skills of Jim Murray and Paul Wing, roads were built, a multitude was sheltered, fed and paid, cameras worked, lights worked (with acetylene lamps), and dams burst on cue.

Geographic and technical difficulties were not the only challenges to the production. Moonshine proved to be the greatest danger to life and property. One night a gunfight broke out. A mountaineer had stolen his brother’s still. There was no bloodshed although Brown almost lost his leading lady.

Robbinsville historian, Mashall McClung, tells of another whiskey-fueled incident. A series of “splash dams,” similar to those used in the logging industry to float logs downstream, had been designed near the headwaters of the Little Santeetlah for the film’s climactic flood scene. Paul had supervised the construction.

The idea was to knock timbers from the splash dams in a sequence to simulate a gradual, increasing tide that would flow by the leading man’s cabin as the courageous Helen Mundy rescues the unconscious Forrest James from the raging waters.

Unfortunately, the Graham County men in charge of the splash dams became bored waiting for the camera set up and began drinking moonshine. By the time Paul Wing signaled for the first dam to be opened, they were so drunk they knocked loose the timbers of all the dams at once. The resulting torrent thundered down Santeetlah Creek hitting Helen and Forrest with a tremendous force, washing them downstream well past their intended mark.

“I feel certain that the look of fear on the young lady’s face was genuine,” said McClung.

Any trouble the mountaineers may have caused was more than offset by their performances on screen. The acting of the amateur players, including Paul Wing, far exceeded Brown’s expectations. And the setting was spectacular. Jim Murray under Brown’s direction captured some of the best outdoor footage of Appalachia ever filmed.

The film premiered at the Cameo Theatre at 42nd Street and Broadway on February 27, 1927, and opened to great critical success. The New York Times proclaimed it, “The most unique motion picture ever made!” Their critic, Mordaunt Hall, extolled the “ethnographic value” of the movie. The News called it, “An almost perfect picture!” The Sun implored, “See it at all costs!”

Stark Love went on to make the lists for The New York Times’ and the National Board of Review’s top 10 films for 1927, in the company of Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings, Victor Fleming’s The Way of All Flesh, Josef von Sternberg’s Underworld, and William Wellman’s Wings.

Karl Brown had won an audience for his film, and Paul Wing had lived through an extraordinary Hollywood baptism by fire which led to bigger assignments.

Meanwhile in San Diego, Peleg had regained his health in 1919 and was once again a prominent figure in the American medical community. As late as 1928 he was being published in medical journals.

13 years after beginning his new practice and nearly 20 years after beginning a new life with his second wife and daughter, he passed away in 1932 in San Diego at age 71. His obituary, printed in the Tacoma Day Ledger, noted he “was a pioneer physician…beloved by hundreds of old-timers who knew his skill and many benefactions carried out in a quiet way.” The article also mentions that Lory Wing’s son Peleg was the last of the Wings residing in Tacoma. He died in 1988.

In 1935 Paul Wing won an Oscar for his work as Assistant Director for The Lives of a Bengal Lancer starring Gary Cooper. Along with his outgoing wife and his beautiful daughters, Paul became a well-liked member of the Hollywood community. He built a house on Rodeo Drive and the Wings entertained a duke’s mixture of friends the like of Amelia Earhart, W.C. Fields, J. Edgar Hoover, Gary Cooper, and Shirley Temple.

In the 1930s, Toby became a sensation in Hollywood. She was known as “the girl with a face like the morning sun.” An original member of Samuel Goldwyn’s musical stock company, the Goldwyn Girls,” her suitors included Hollywood royalty and the cream of New York society –Maurice Chevalier, Franklin Roosevelt, Jr. , and Albert Vanderbilt.

However, in spite of her great beauty, she was a victim of poor management. Her roles became decreasingly important. In 1938, she married the famous aviator Dick Merrill and retired from the screen at the age of 23.

Yet, due to the hundreds of glamour shots which were taken of her in the thirties, she rivaled Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth as the G.I.’s favorite pinup girl during the World War that would continue years after her last film.

Throughout the family’s success, Paul Wing continued to be well grounded. During his peak Hollywood years he even served as a volunteer R.O.T.C. instructor at Los Angeles’s Lincoln High School.

Perhaps this played a part in his decision to re-enlist when he saw war was imminent. After training young men to serve their country perhaps he felt an added responsibility to join them when the Army requested his services with aerial reconnaissance in the Philippines. He joined the Signal Corps in 1940 with the rank of Major, and after a short assignment as instructor at the Fort Monmouth, New Jersey Photographic School, was assigned to General Douglas MacArthur’s staff as executive officer to General Spencer B. Aiken.

When the Japanese 14th Army began their invasion of the Philippines on December 8, 1941, Paul Wing was away from headquarters on Bataan assisting in building a road at an air strip. Consequently, he joined the desperate defense of the peninsula with his fellow soldiers from January 7 through April 9, 1942 when Major General Edward P. King surrendered his troops to Major General Kameichiro Nagano.

The surrender followed months of bloody fighting against staggering odds with scant food and munitions as General MacArthur’s famous Plan Orange-3 fell apart with no hope of support from the crippled Pacific Fleet. MacArthur sailed away in a PT Boat for Mindanao, leaving the defenders behind, later issuing an order to General Jonathan M. Wainwright at Corregidor:

I am utterly opposed under any circumstances or conditions to the ultimate capitulation of this command. If food fails you will prepare and execute an attack upon the enemy.

The final blow to Bataan was a constant 6 hour bombardment by 100 Japanese planes and 300 artillery pieces of the Mount Samat fortification from early morning to the mid afternoon of April 3.

Corregidor fell a month later thereby bringing the defense of the Philippines to an end.

So, at 49 years old, after enduring one of the most horrific battles of the war, Paul Wing joined 60,000 Filipinos and nearly 15,000 American soldiers, most starving and disease-ridden, on the 90 mile march from Mariveles to captivity at Fort O’Donnell in the Tarlac province, a camp which had been prepared to receive 25,000 prisoners of war. This came to be called The Bataan Death March.

Out of those who began the march, thousands died before reaching the prison camps. The exact number of casualties is impossible to determine but conservative estimates are between 6,000 to 11,000 men.

Again, photography played a role in Paul Wing’s life. He concealed a camera during the march which he used to secretly photograph the conditions of the men and the atrocities they suffered at the hands of their captors.

Eventually, Paul was sent to Cabanatuan where fellow P.O.W. Sergeant Abie Abraham recalled that he was highly respected and liked by the men. “I washed his clothes and brought him food…He stayed in relatively good physical condition during our captivity…He was a gentleman.”

Interestingly, and this story speaks to the stature that Paul Wing had achieved in his profession, his son Paul Jr. on hearing that his father had been captured, lied about his age and enlisted in the Marines at 15 years old. His mission was to get to the Philippines and rescue his father.

On learning what had happened, Martha called her good friend J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Paul Jr. was found and brought back home. When he reached age 16 in December of the same year, he somehow convinced his mother to sign a consent form and he again joined the Marines. His assignments did not take him to the Philippines.

Paul Wing was a P.O.W. for nearly three years until rescued January 30, 1945 by U.S. Army Rangers, Alamo Scouts and Filipino guerrillas. This was the famous Raid on Cabanatuan written about by Hampton Sides in Ghost Soldiers and later made into the movie, The Great Raid.

As astonishing as it seems, Paul took photographs during the raid as the gunfight blazed between his liberators and the Japanese guards.

When Paul and the rest of the men were transported to safety, their doctors and nurses sensed a feeling of sadness and apprehension among the men. Eventually, it became apparent that the former prisoners of war felt they would return to the United States in disgrace. They believed the American public would consider them cowards for not fighting to the death at Bataan. Even General Wainwright, on meeting MacArthur in Tokyo Bay at the signing of the peace treaty in September of 1945, wept and begged forgiveness of his former superior for surrendering Corregidor. Wainwright was certain that a court-martial awaited him.

James Webb recollected his feelings on witnessing this scene:

Wainwright had carried the load, had fought the impossible fight, suffered the insufferable, borne the unbearable. And here he was begging for forgiveness from the very man who had left him and the others behind to suffer death, starvation, and captivity.

According to his family, Paul Wing never completely overcame his feeling of shame for surrendering. Sadly, this emotion is apparent in the news wire photo of his liberation. He avoids looking at the camera as his former superiors smile broadly, thankful for his rescue.

Far from returning in dishonor, Paul was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, and, for his actions at Bataan and for secretly documenting the atrocities at Cabanatuan, he was awarded the President’s Citation, Legion of Merit, the Purple Heart, the Oak Leaf Cluster, the Philippine Government Decoration, and 6 battle clasps.

Understandably, when he returned home to his family he was a changed man. The tremendous ordeal had taken its toll on his heart. Though in failing health, he bought a beautiful farm in Mathews, Virginia called Shadecliff. There he farmed, made furniture and enjoyed nature and the out of doors with his wife and family. He became a much beloved member of the Mathews community, attending the Episcopal Church, serving as a Royal Arch Mason at the local lodge and a Commander of the American Legion Post.

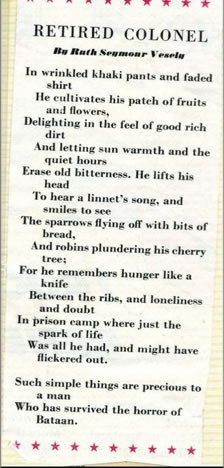

A poet, published in national magazines of the 1950s, Ruth Seymour Vesely wrote this about Paul and his life in Mathews:

Paul Wing died in 1957 at the age of 65.

Paul Wing died in 1957 at the age of 65.

Paul Wing, as a young man disowned by a disapproving father, went on to live a life of accomplishment, courage, honor and patriotism – a credit to the Wing Family of America and to the city of his birth.