AN OSCAR-WINNER’S CONNECTION TO TENNESSEE

At this writing, the 83rd annual Academy Awards show is being planned for the $94 million, 3,400-seat, 136,000 square foot Kodak Theatre in Hollywood. This is quite a contrast to the ceremonies’ early years when a small banquet was held in the Cocoanut Grove of the Ambassador Hotel.

On such an occasion in February 1940, a 44 year-old African American woman from the boards of vaudeville triumphed against the likes of Olivia de Havilland, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Edna May Oliver, and Maria Ouspenskaya for the Best Supporting Actress of 1939. Her name was Hattie McDaniel and she was honored for her unforgettable portrayal of Scarlett O’Hara’s “Mammy” in Gone With the Wind.

It’s not widely known but this Oscar-winning actress has a connection to our very own Lincoln County – to Boonshill, to be specific. Her father, Henry McDaniel, was one time a slave of John F. McDaniel (1807-1861), son of Fielden McDaniel (1781-1840), one of the Virginians who first settled Petersburg, Tennessee.

Henry McDaniel was born on the Spotsylvania County, Virginia plantation of Robert Duerson around 1838. He was never sure of the exact date. Additionally, he had very little recollection of his parents for, as a youngster, he was often selected for labor that separated him from his mother and father, such as weeding the grounds and taking care of livestock, while they worked in the fields.

Henry McDaniel was born on the Spotsylvania County, Virginia plantation of Robert Duerson around 1838. He was never sure of the exact date. Additionally, he had very little recollection of his parents for, as a youngster, he was often selected for labor that separated him from his mother and father, such as weeding the grounds and taking care of livestock, while they worked in the fields.

Then, by age nine, came a more profound separation. He was sold by Robert Duerson to a Lincoln County slave trader named Sim Eddings, along with his 6 year old brother and 11 year old sister. Providentially, all three were bought on the auction block in Fayetteville by John McDaniel in the Fall of 1847.

John McDaniel was from a well-regarded family, the most notable member being his younger brother Coleman Adams McDaniel (1823-1896). The Nashville Christian Advocate described him as “a tall, slender rather delicate-looking” man,” but looks can be deceiving. When Henry arrived at the farm, Coleman was fighting the Mexican War as a 3rd Lieutenant in a company of 83 men called the Lincoln Volunteers. They were commanded by his wife’s cousin Captain Pryor Buchanan. The Buchanans were among the first to record land grants in Lincoln County, dating back to 1794. Coleman’s father-in-law, Andrew Buchanan, was a successful merchant and planter.

Among other engagements, the Lincoln Volunteers fought at the Battle of Monterey, suffering several casualties.

Following the war, Coleman — like many other Mexican War veterans — joined the 1849 California Gold Rush, trying his hand at prospecting (evidently with little success, for soon he returned to Tennessee).

Back in his home State he launched a career in politics, becoming a State Legislator then, with the coming of war he helped form the 44th Tennessee Infantry Regiment, serving as its commanding officer with the rank of Colonel.

At the bloody Battle of Shiloh, the 44th entered the fray with “470 men in line.” the next morning only 120 answered roll call. Coleman, in particular, was recognized for gallantry after being wounded capturing an enemy battery. There are accounts by his men attesting to the fact, though severely wounded, he continued command. Nearly 24,000 out of 111,000 fighting men of both armies were either killed, wounded, or missing after 2 days of combat.

Henry recalled that life was hard before and during the war on the McDaniel farm. He was put to work picking and husking corn, chopping wood and plowing fields. Food was scarce, clothing was course and ragged, and housing was barely shelter. For 10 years he worked for John, then was lent out to others, probably relatives of the McDaniels.

In 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, slaves flocked to the lines of the invading Union Army who periodically occupied Lincoln County as early as the Fall of 1862. Henry was among those who joined Company C of the 12th United States Colored Infantry whose first charge was to build and protect the Nashville and Northwestern Railroad. Later, however, the 12th took part in some of the fiercest fighting of the war. In the Battle of Nashville, in December of 1865, their racist commanding officer, General George H. Thomas, hurled the 12th into the teeth of rebel guns defending Overton’s Hill. The maneuver was a suicidal feint to draw Confederate General Hood’s attention while white troops outflanked his army. The black regiments were said to have lost more than 64% of their number in the performance of this action. Their bravery helped turn the tide of battle and break the back of Hood’s Army of Tennessee.

During battle, Henry’s jaw was shattered when a cannon shell exploded near his position. This and other injuries plagued him for the rest of his life. He was a semi-invalid by his sixties.

During battle, Henry’s jaw was shattered when a cannon shell exploded near his position. This and other injuries plagued him for the rest of his life. He was a semi-invalid by his sixties.

The ex-slave did not fight against his former master at Nashville. John had died during the first year of the war. In late May of 1864, Coleman McDaniel returned home from Georgia seriously ill. However, he recovered to live another 31 years.

Henry also returned to Boonshill after the war but was greatly disillusioned by the continuing lack of freedom for his people. In an earlier Petersburg News, mention was made of the rise of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction, a violent response to Governor Brownlow’s Republican policies. In Lincoln County, in 1868, the night riders broke into the home of an ex-slave, Richard Moore, stripped him to his waist, tied him to a tree, and whipped him 175 licks with a leather strap and buckle. They told him that he “ nor no other colored man should vote in the Presidential election.” They told him to take his bloody shirt to the Tennessee Legislature to show them what would happen to “Radical Republican” blacks who tried to vote – which he did, which led to an increased military presence in Lincoln County.

In the same year, a report recorded with the Tennessee Freedman’s Bureau described a similar attack against Henry McDaniel and two other ex-slaves while working in a place referred to as “Sinclair County”.

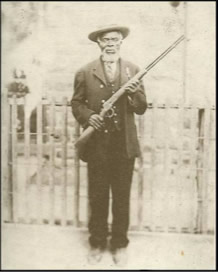

Around 1875 Henry left Boonshill then, five years later, Tennessee. By 1915, Henry had moved his family to Denver, Colorado where, one day, he received in the mail a Civil War Veterans Questionnaire, and that is how we know about his life in bondage and his service in the War. Helping him to complete this extensive, multi-page survey was his daughter Hattie, who 25 years later would be awarded a golden statuette for portraying a Southern slave.