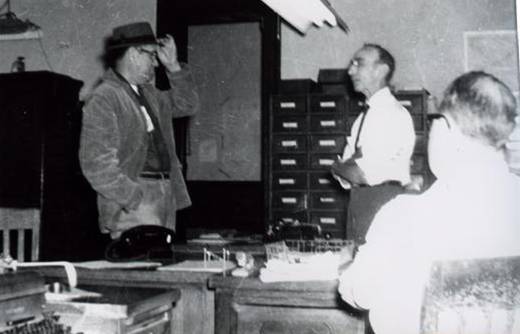

My dad was the Railway Express agent in Columbia and his office was in the old depot. In his long career, he shipped all kinds of livestock, everything from rattlesnakes to elephants – literally – without use of a forklift. It was all done with brawn, brain, and nerve.

A regular cargo was homing pigeons, usually shipped in custom woven basket crates from Evansville, Indiana or Louisville, Kentucky. Not only were the birds a messy, malodorous parcel, they came with a written set of instructions which entailed an oft-repeated ceremony.

“Sometimes a crate of birds would arrive on the midnight train,” says my dad. “They were to be released at 7 a.m.

“When I opened the envelope, occasionally, there’d be a $5 tip. Especially if it was an early morning flight.

“Sometimes they’d come in at 10 a.m. and I would release them at noon. I’d walk out to the middle runway, set down the special-made baskets, and release them all at once.

“There’d usually be forty birds in the baskets.”

A homing pigeon is a remarkable creature. Most of their talent is God-given but there’s training involved, as well. The God part comprises their supernatural eyesight and ability to spot landmarks going and coming. It also, believe it or not, has to do with an astonishing sensitivity to ground radiation. In that respect, they’re like heat-seeking rockets.

The human training part relies a lot upon bird feed. Young pigeons are taken out of their lofts, then put back at feeding time. They begin to associate returning to the loft with a good meal of corn and peas. Distances increase from a few feet, to a corner of a roof top, to miles and miles.

“We were never supposed to feed ‘em,” says my dad.

As a side note, I can remember as a kid, an association with the Railway Express Company and the noble homing pigeon. Back in the fifties and the early sixties, the renown and bravery of this bird was fresh in the public memory.

Pigeons had been used in war time to send messages across enemy lines – by both sides! This practice goes back to at least the Crusades.

In peace time, more than one crew of a crippled ship was saved by releasing a homing pigeon to report their location. In 1922, eleven members of the motor launch Crawl was rescued in the Pearl Islands in this fashion. In the late thirties, a fishing crew off Freeport, Long Island was rescued during a storm in Great South Bay when they released 40 homers who found the local Coast Guard.

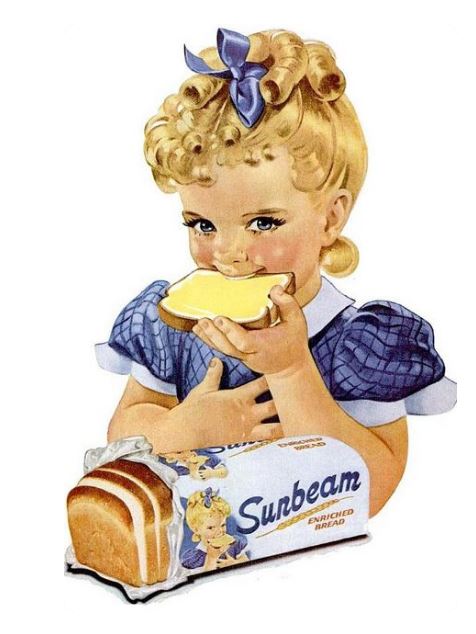

Anyhow, back to my remembrance of the Express company’s association with the pigeon, each Express truck carried billboard panels on each side. They usually were paid advertisements for companies like Kraft Foods or Purity Milk or Sunbeam Bread.

By the way, at five years old, I was in love with the little blond Sunbeam Bread Girl, and, when I was a fifty-year-old man, I met her at a sporting clays tournament outside Atlanta, her hometown. I told her I’d been in love with her and she seemed really impressed before she reloaded and blew two clays out of the sky.

But I digress.

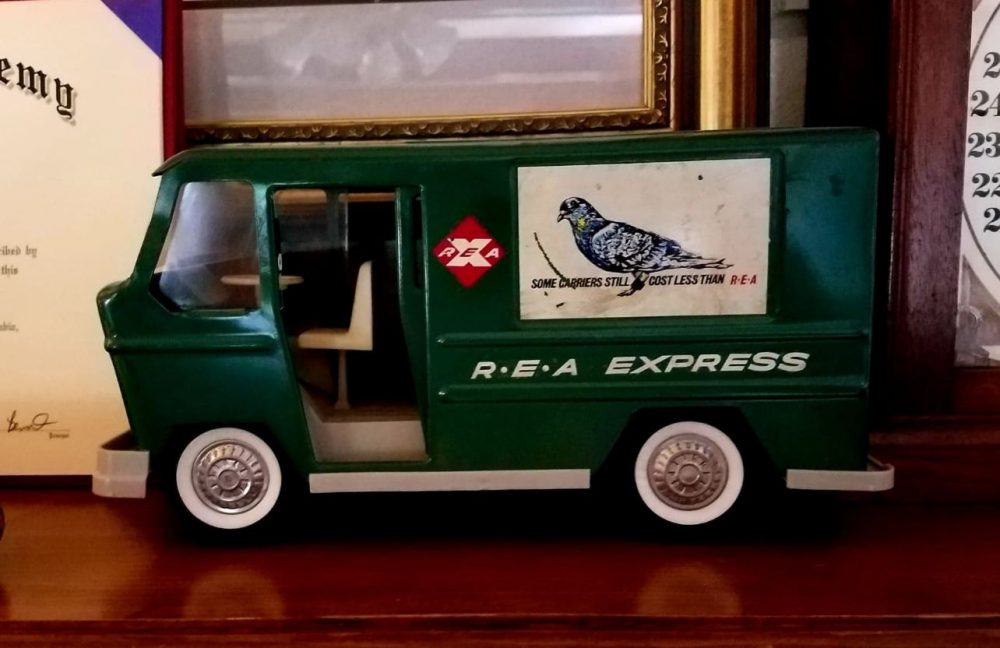

Returning to the truck billboards, when I was a kid, I washed the delivery trucks — the big ones and the small ones. Often the trucks would feature ad campaigns for the express company, itself. One memorable graphic was of a pigeon and the caption, “Some carriers still cost less than REA.”

My dad was given a toy Tonka truck during that time which features that very billboard.

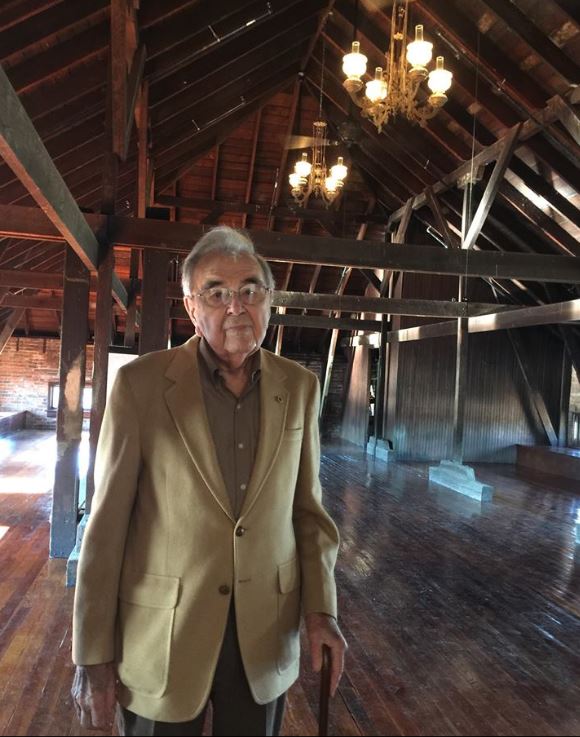

Speaking of my dad, when he was on that concrete runway, early in the morning, releasing those birds, he would watch their flight with much fascination. He was a country boy and today, at 96, he still has a love and an affinity for nature.

“Those birds would fly straight up, then circle the town to get their bearings. Meanwhile, the fat wild pigeons who dwelled under the railway platform and the feed silos of Columbia Mill and Elevator, a few yards down the track, would wake up. They’d want to know what all the commotion was about.

“They’d take to wing and try to follow the young, slim birds, but after a short distance, they’d drop off and the homers would form a sharp V pattern and sail to Louisville.”

A racing pigeon can fly nearly 80 miles per hour and some have been clocked past 90. Louisville, being more than 200 miles away, the birds would arrive between eleven and noon.

“A man would call me when they arrived to verify the time I released them,” says my dad. “He was always real polite and thanked me.”

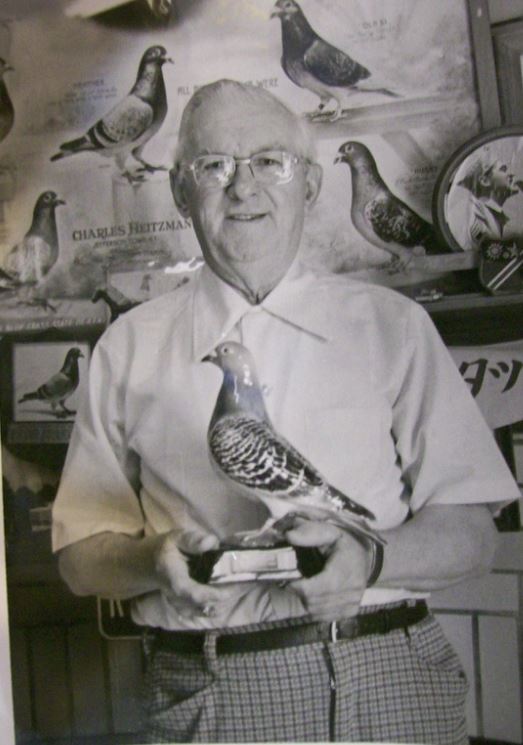

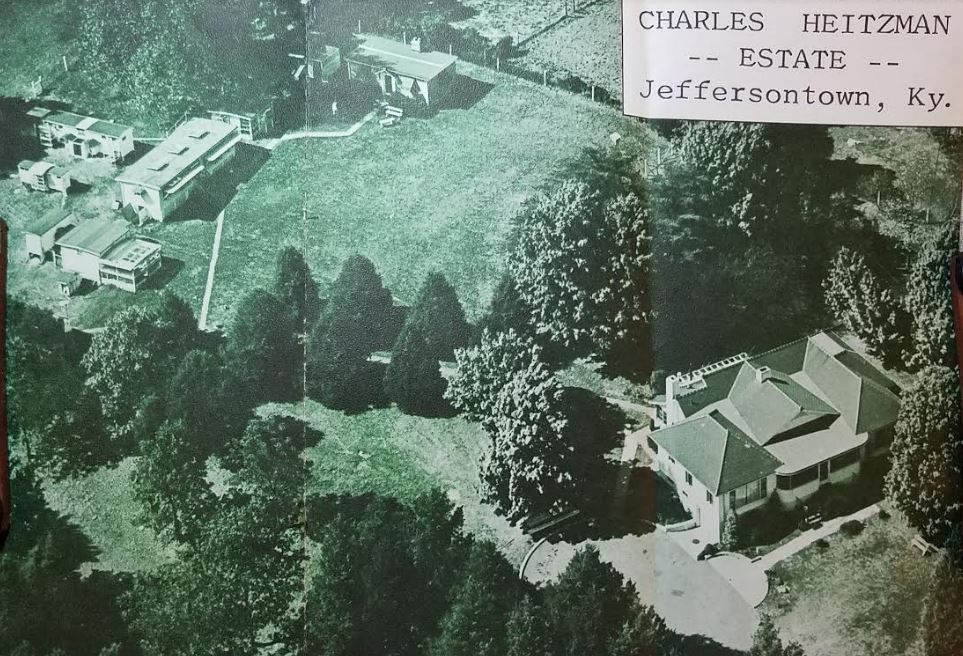

The man likely was the secretary of one of the racing pigeon clubs. Although another person he had contact with was Charles Heitzman of Heitzman Bakery fame. He was considered the Godfather of Racing Pigeons in the United States, having joined the Louisville Racing Pigeon Club in 1912 at the age of fifteen. During the heyday of my dad’s participation, Mr. Heitzman would have been in his sixties.

Many years after my dad retired from REA, I happened by the depot during one of its aborted restorations before the Hills bought it and finished the job in magnificent fashion. A workman had gone to lunch and propped the door to the waiting room open with a pain bucket.

Being curious about what the old building looked like inside, I wandered inside. It was very dark and cobwebby as I navigated the old winding stairs up to the living quarters of where the caretaker’s family once lived.

When I reached the landing, there was the big bay window – in about a 6 foot by 4 foot frame. It was very dark. The glass panes were covered with fifty years of dirt and cinder dust, but slender beams of daylight shone through broken glass.

It seemed to me there was a little rustling noise and almost a “chirping” sound on the landing. I attributed that to the condition of the boards.

Suddenly, about forty fat pigeons exploded from the floor and the sill – descendants of those worthless, lazy Columbia Mill and Elevator foul.

I don’t know how fast I raced up those steps but I believe, if I could have kept up that speed, I could have beat any bird to Louisville.