My grandfather Bob White was the son of a Confederate cavalryman. His way of life in the country had been pretty much the same as it had been when his great-grandfather Lewis first came to Maury County in the early 1800s and didn’t change considerably through the time my own dad grew up in the 1920s and ‘30s. For instance, my dad was about fourteen before the federal Public Works Administration brought electricity down the road.

Before that, the White family lit their house at night with kerosene lamps and cooked their meals on a woodburning stove or in the fireplace using a crossbar, hooks, and cast iron pots or skillets and a grate. Their refrigerator was a tongue and groove stall in the stable where sawdust was piled about three feet high. That’s where they kept potatoes, turnips, sweet potatoes, and other vegetables that needed preserving. On Saturdays they would drive into town, buy a 50 pound block of ice from the ice plant, wrap it in a grass sack, tie the sack on the back bumper of the A-Model Ford, and haul it back to the sawdust stall. Ice would keep in the sawdust all week. They had iced tea all week – and a lot of company on Saturday nights who admired iced tea and my grandmother’s cooking.

For entertainment, my grandmother and my aunts played piano and my dad played guitar with some of his buddies. Bob was a great banjo player but would only play “when the right one would beg him to.”

“He could play a guitar, too,” said my dad, Jack White. “He would tune it to an open banjo key and play the fire out of it.”

There were six in the household – my grandparents Bob and Hattie White and their children, in order of birth, Tom, Kathryn, Jack and Margaret Dee.

Front row: Tom, Kathryn, Jack, Douglas, and Ann Louise White. Back row: Bob, Margaret Dee, Hattie, Mary, Katie Belle King, and Fred White

All were great singers as well as musicians except for Tom who was a critic. “I wish y’all wouldn’t play all them old forsaken songs.” His aim was to say “sacred songs,” but forsaken was closer to his true feelings.

The Whites were for the most part subsistence farmers, growing crops to feed themselves, with some surplus crops like tobacco that put a little money in the bank. Neighbors helped neighbors and traded out work to bring in hay, cotton, tobacco, and whatever else needed doing.

When my dad was a teenager he put aside $31 from his tobacco crop and bought a battery radio from his cousin Clyde Cheek whereby, instead of homemade music, the family could listen to the Grand Ole Opry over clear station WSM.

“Clyde didn’t tell me the speaker rattled,” my dad said. But being a natural-born mechanic, he took the radio apart, slid a sheet of paper between the frame and speaker and it worked like a charm. So, Saturday nights neighbors not only enjoyed iced tea and my grandmother’s sugar cookies (or, tea cakes, as she called them), they also delighted in DeFord Bailey making train sounds on his harmonica, Uncle Dave Macon strumming the banjo, and Roy Acuff wailing about The Great Speckled Bird.

The White House was a popular place in the country. And there were many great characters who lived out their way.

One family was the Freelaands. Sam and Annie Freeland and their family lived with Sam’s bachelor brother Tom. My dad would walk over to the Freelands to get his hair cut by Tom every couple of weeks.

On one occasion, it was during a spell when sheep were being poisoned by eating a wild “tar weed” that would cause their heads to swell up.

One day, Tom was cutting my dad’s hair while Jack sat on a wood plank placed on a galvanized milk can in the front yard. Tom was a little hyper and he would circle round and round as he nervously snipped away.

For whatever reason, Tom had his overalls rolled up above his boots that day, revealing his spindly little legs.

Miss Annie sat on the front porch observing. Finally, she spoke to my dad.

“Jack,” she said. “Look at Tom’s legs…You reckon he done ate some tar weed…?”

“She knew that would make me laugh,” said my dad. “And there was jumpy Tom with a pair of scissors in his hand!”

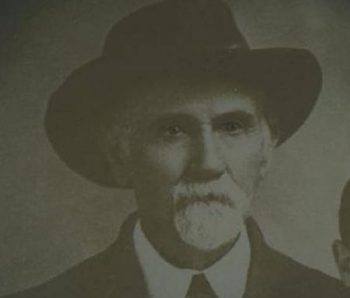

I was four and a half years old when my grandfather Bob White died but nearly sixty years later I recall him vividly. He looked like a Confederate soldier just like his old daddy. In fact, he wore gray suits with vests and wide-brimmed Stetsons. He was rapier thin and ramrod straight and he most of the time wore a stern expression. I probably was a little afraid of him if I was to admit it, but I loved him and wanted his friendship.

His wife Hattie lived until I was forty and I loved her to death. She was the finest and most kind-hearted woman I ever knew but she had an expression whenever I was winding off the straight and narrow. She’d say, “Now, cut out that old foolishness!”

I have a feeling from my own experience and from stories told by my dad that Bob White did not abide foolishness of any stripe.

He came up hard. After the Civil War, his father James Lewis White was a deputy sheriff but also a profligate gambler and hard drinker.

Late at night in the dead of winter, the old Cavalryman would ride up to his home after a long night of cards and dice and call for my grandfather. Bob, still a young boy, slept in the attic of the house with his brothers Cleve and Fred. He was the next to last child of ten born to James Lewis and Ophelia Tennessee Davidson White. By the time he was ten, his older brothers were already grown and out of the house.

James Lewis’s shouts and cursing would awaken him. Bob would throw on a coat and boots, climb down the attic ladder, grab an ice pick and walk outside into the bitter cold. He was used to the ritual of chipping the ice off his drunken father’s boots and stirrups where he could dismount.

Bob probably was a rounder himself as a young man. He was known as a champion buck dancer and, in a time and place where people married young, he didn’t marry until he was 33. In 1918, he wed his brother’s 22 year-old sister-in-law, Hattie Mitchell White – of no relation.

Hattie was of an Irish line of Whites who came to Maury County from Lawrence County, whereas Bob’s family was from England, then Virginia, before his great-grandfather Lewis White came to Maury County. Eventually, Lewis and all his sons but one moved to Jackson, Tennessee to establish cotton plantations near that town’s railroad hub. Bob’s grandfather William stayed behind.

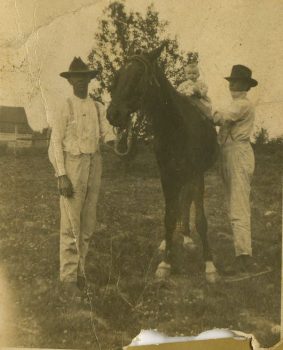

Hattie was probably pretty vulnerable when Bob began courting her. I never knew her to be jealous of anyone but in the picture below from the wedding of her younger sister Mary to Bob’s younger brother Fred, she looks put out. Hattie married Bob three months after this photograph was taken.

By the way, the heifer in the picture is a gift to the lovely couple from Hattie’s father William Brantley White, proud breeder of prize Jersey cattle.

Bob was very wise in the ways of farming. Fred often came to him for advice, once about Irish potatoes.

“Bob, I can’t grow Irish potatoes in the hard ground on my place. Do you have a spot on your farm where they might grow?”

Bob grabbed a hoe and climbed the tall, heavily-forested hill behind his barn until he found a wide bare patch among the trees covered with leaves. He hoed furrows of about five inches deep and told Fred to plant his potatoes. This was in February.

Fred said, “You think Irish potatoes will grow in these woods?”

“Plant your potatoes, Fred,” said Bob.

“Come Spring, you never saw the like of potatoes,” said my dad.

Bob also was an excellent horse and mule trainer – which on occasion brought out his creative side.

Once, while he was riding down a path, a snake crossed the road, startling his horse and causing the animal to rear up. Bob jumped off his horse, tied him to a tree, then caught the snake by the tail and cracked him like a bullwhip, causing the snake’s head to pop off. He then tied the snake to the saddle and rode the horse all day.

Evidently, the horse learned snake tolerance.

Bob obviously was not afraid of snakes. He kept a long black corn snake in his crib to keep rats away until my dad requested he use another method.

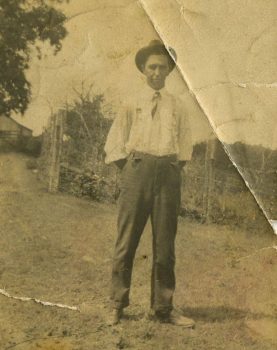

My dad inherited Bob’s gift for training horses and, additionally, was an exceptional dog trainer – not only for bird and squirrel hunting purposes but also for entertainment.

He had a squirrel dog named Tip, a solid white fyce except for a liver spot over his left eye. He was part Rat Terrier with the other part left to speculation.

There was a white plank fence that surrounded the farm. The top plank was slanted to let the rain run off.

My dad would command, “Tip! Up!” And Tip would hop up on the top plank and run the fence. Then my dad would twirl his finger in the air and Tip would twirl around and run in the other direction.

My dad was big on hand signals with dogs – especially bird dogs. He hated to hunt with anybody that hollered at dogs all day.

I’ve written about Tip before but another more detailed version of his demise follows:

Bob’s neighbor, a sheep farmer named Everett Cheek had a German Shepherd dog he was very proud of. One day he saw Jack and Tip in their adjoining fields and said, “Jack, you better keep your dog close. This dog will surely kill yours.’”

Tip was a rather small dog but very muscled up from squirrel hunting and plank fence calisthenics. Abruptly, the German dog broke loose from Everett and attacked Tip…and proceeded to get roundly thrashed.

The shame and humiliation of having his prize dog pounded by a diminutive half-breed did not set well with Everett. Before too long, he was over to Bob’s complaining that Tip was killing his sheep – and likely badgering Bob to pay for his losses.

This went on for awhile before Bob came to Jack and said, “Son, you’re going to have to put down Tip. He’s killing Everett’s sheep.”

Of course, my dad was very upset. He told my grandfather about the dogfight and he even went to Everett.

“Tip and I have walked right through your flock. He doesn’t even look at a sheep. Check his mouth. You won’t find any wool.”

Everett was not moved. So, my dad leashed Tip, walked to the barn, and handed him to Bob.

“If you want him killed, you’re going to have to do it or find somebody else. I can’t do it.”

So Bob took Tip to the woods and shot him.

Later, it was found that Everett’s Shepherd was the sheep killer.

“I never got an apology from anybody,” said my dad.

Across the road from the house, high on a hill there was the Philadelphia Church of Christ and the Lickskillet School on a dirt road which is now paved and named Fred White Road.

It has been rumored that former members of Company F of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry, my great-grandfather’s old bunch, kept their Klu Klux Clan robes in the attic of the church.

Before anybody gets their shorts in a wad, it should be known that the Clan originally was a movement against Reconstruction. The Union occupying force had stripped all rights from ex-Confederates, especially officers – and you didn’t take anything away from the men who lived at Park Station. They were ready and able to take it back. After the organization devolved into baser activities, most left – including General Nathan Bedford Forrest. In 1869, after a year serving as Grand Wizard, Forrest issued a General Order Number One: “It is therefore ordered and decreed, that the masks and costumes of this Order be entirely abolished and destroyed.”

Lickskillet, like a lot of schools in the country, would host fiddler contests which also would feature other contests for guitar playing and buck dancing, for instance. Although, my dad and his siblings went to Bryant Station they went to the fiddler’s contest one night at Lickskillet. My dad was about fourteen years old.

When the buck dancing contest was underway, a young boy by the name of Blalock seemed to be the favorite. Then, someone noticed Bob in the crowd.

“Bob White, get up there and dance!”

Some of the older people in the crowd remembered him from his younger days. Pretty soon there was a groundswell of enthusiasm and shouting for Bob to dance coming from the old timers and curious young people alike.

Finally, Johnny Adams the school principal came up to Bob. “Mr. White, please do me a favor and get up there and dance.”

So, reluctantly Bob took the stage. But, once he was up there and the fiddles started, he put on a show. He went through all his old routines, including his heel and toe “driving pigs” step. The crowd went crazy. Many of the younger people who knew Bob from church or at Galbreath’s Store had no idea he could dance.

“He never moved from his waist up,” said my dad. “He was steady as a duck on the water. But his feet were light and fast as lightning.”

At the end of the performance, he received tumultuous applause and, of course, won the prize – a bag of meal.

As Tom carried the bag of meal to the A-Model, Bob noticed the Blalock boy walk away dejected.

“Who is that boy?” asked Bob.

“That’s Kip Blalocks’s boy,” said my dad.

Bob grew quiet. Kip Blalock was a poor crippled man who lived in an old rundown house in the country with his family.

“If I had known he was Kip’s boy, I never would have gotten up there,” he said. “That family needs that meal.”

Some of the guilt faded away for him when the White family returned to the A-Model later that night.

Someone had stolen the prize.

When my grandfather died, my dad bought the old homeplace. I was four.

I loved the old place with the purple Tennessee irises growing along the white plank fences and the quail singing in the pasture.

“Bob White! Bob White!” they would call.

And, at four, I would reply, “He’s dead! We had the funeral at the Philadelphia Church of Christ!”